Arbor Day was April 28th, and there’s no better time to celebrate one of the most beloved elements of the natural world. Every single tree tells an epic story—if we know how to read it!

How to Read a Tree from New York Times-bestselling author Tristan Gooley uncovers the marvelous wonders of branches, trunks, canopies, and more, unveiling the clues hidden in nature’s most majestic feature. Tapping into this silent language of trees sharpens our understanding of the environment—to read a tree is to paint a unique portrait of the surrounding land, soil, weather, animals, people, and even time.

How to Read a Tree from New York Times-bestselling author Tristan Gooley uncovers the marvelous wonders of branches, trunks, canopies, and more, unveiling the clues hidden in nature’s most majestic feature. Tapping into this silent language of trees sharpens our understanding of the environment—to read a tree is to paint a unique portrait of the surrounding land, soil, weather, animals, people, and even time.

How to Read a Tree is a must-read for every nature lover and outdoor enthusiast. To begin this eye-opening adventure, read below for an exclusive excerpt from How to Read a Tree, publishing May 2nd.

Whether in a forest, city, or your own backyard, you’ll never see a tree the same way again. Enjoy!

The Art of Reading Trees

AN INTRODUCTION

Trees are keen to tell us so much. They’ll tell us about the land, the water, the people, the animals, the weather, and time. And they will tell us about their lives, the good bits and bad. Trees tell a story, but only to those who know how to read it.

Over the years, I have enjoyed collecting every meaningful characteristic of trees that we can observe. It started with natural navigation and an obsession with the ways in which trees can make a compass—they grow bigger on their southern side, for example. This developed into a fascination with how trees make a map for us: The trees that grow by rivers are different species from those on hilltops. And this blossomed into a curiosity about the subtler clues, the patterns that hide in front of our eyes.

Do two trees ever appear identical? No, but why? Every small difference in a tree’s size, shape, color, and pattern reveals something. Each time we pass a tree we can note a unique feature and read it as a clue to what that tree has experienced and what it reveals about the spot we stand on. A tree paints a picture of the local landscape.

The smallest details open bigger worlds. You notice that the leaves on a tree have a strong pale line down their middle and recall that this is a sign of water nearby. Moments later you see the river. Many trees that thrive near water, including willows, have that distinctive white rib on their leaves—they look like they have a stream down their middle.

My aim in this book is for us to immerse ourselves so deeply in the art of reading trees that we learn to find meaning where few would think to look. And once we have seen these things it’s impossible to unsee them— trees never appear the same again. It’s a joyous process.

We’re about to meet hundreds of tree signs. I encourage you to go and look for them as this is the best way to become part of their story. It will help you read, remember, and enjoy them for the rest of your life.

The Magic Isn’t in the Name

The art of reading trees is about learning to recognize certain shapes and patterns and understand what they mean. It is not about species identification. The names of trees are a lot less important than many people think.

Individual species exclude people and tie us to certain places or regions—there are no native species common to both north and south temperate zones and possibly only one that Eurasia and North America share: the common juniper. There isn’t a soul on the planet who can identify the species of most of the trees on Earth on sight. There never has been and never will be. It would take more than one lifetime to learn how to identify each willow species on sight, never mind that there are perhaps a hundred thousand other tree species. Recognizing tree families can be helpful, but individual species, not so much.

You will see I refer to common families, like oak, beech, pine, fir, spruce, and cherry. They are widespread. Most people can recognize a few of them and the others are easy to add. If you are totally new to trees and don’t yet recognize any families, like oaks or pines, I have included some tips at the end of the book. Unless otherwise stated, we are considering the north temperate zone, which includes most of the populated parts of Europe, North America, and Asia.

In each case I am referring to broad traits within the families, not hard and fast rules that apply to every species or subspecies. If you can think of an exception, I congratulate you but hope you can appreciate that it is an exception that proves the general rule. A book that covered every such exception would be a dull book indeed and would quickly be returned to the tree pulp whence it came.

Some trees have many different names, and the “correct” one depends on which culture you ask. Indigenous peoples find remarkable meaning in plants but have little use for Latin. Whatever we call a tree, it can’t change what we see or what that means. The fascination lies in discovering the global language of natural signs. I love the idea that we can recognize patterns in nature that someone on the other side of the world would also know, even if we don’t speak a word of each other’s language. Our ancestors’ fluency in reading nature’s signs must predate even the earliest of spoken languages by tens of thousands of years.

The word magic has more than one meaning. It can mean to perform tricks for entertainment. But it is also the possession of extraordinary powers, the ability to make things happen that would usually be impossible.

The roots of a tree will show us the way out of a wood, even when we don’t know its name.

A Tree Is a Map

Where Conifers Call the Shots

I made my way north along the gentlest of rolling ridges in the mountains of the Sierra de las Nieves National Park in southern Spain. There was no path, but I picked dusty threads that twisted between rocks, gorse bushes, and thistles. The heat from the August sun rose off the land.

The sharp rocks meant I had to scan the ground, and every couple of minutes I’d pause and lift my eyes to take in the land around me. This is an old habit: When a path is difficult, we see too much ground, and when it is easy, we see too little. If you want a full picture of the land you move through, it helps to look down on good ground and up on bad terrain. But pause before looking up from a difficult path or your face will meet the rocks. When passing trees, tricky paths mean you see the roots and miss the canopies; easy paths mean you see whole trees, but miss the roots.

The scan paid off. Down in the gentlest of dips between hills I saw a green beacon, a clump of trees that didn’t fit the pattern at all. I made my way down toward the greenery. Suddenly I could hear and see more birds, and some pale butterflies danced across my view. There was a slight change in the smell of the air. I took in slow, deep lungfuls. It wasn’t a specific odor, just the familiar rich whiff of verdancy and decay. Then I noticed the animal trails start to funnel together and intertwine, like strands of a rope. Minutes later I was standing under a grove of magnificent walnut trees, the only ones for miles around. Near it there was a stone watering trough for goats, a confusion of their hoof prints in the wet mud around it.

The trees had signaled change: They had led all the animals, including me, to water.

Trees describe the land. If the trees change, they are telling us that something else has also changed: There has been a shift in the levels of water, light, wind, temperature, soil, disturbance, salt, human or animal activity. When we learn how to spot these changes, we have the keys we need to see the map the trees are making. We shall meet the keys soon, but first we will tune into two of the big broad changes we will see.

WHERE CONIFERS CALL THE SHOTS

After leaving the walnut grove, every large tree I saw for the rest of my walk in the Spanish mountains was a conifer. There is a good reason why.

A very long time ago, there wasn’t much going on, but then evolution rolled up its sleeves. Algae appeared in the sea, then mosses and liverworts appeared on land. Soon, and by soon I mean a few hundred million years later, ferns and horsetails were spreading their simple fronds above the mosses.

Evolution is a genius at solving problems. It worked out that seeds meant you could give offspring a start in a different location and that led to most of the plants that grow today. Next it discovered that a woody trunk allowed you to stay above the competition for many seasons without starting at ground level again each year. Boom! Trees were born.

The earliest trees belong to the gymnosperm group of plants and include conifers. They bear their seeds in cones. About two hundred million years later another tree family evolved, the angiosperms or flowering plants, and this group includes most of the broadleaf trees. They are much more diverse in appearance than conifers but tend to have flowers that are easy to see and bear seeds in fruits. Most conifers are evergreens and most broadleaves are deciduous, losing and regrowing their leaves each year.

We can normally easily identify which of these two main groups we are looking at. If a tree has dark, needle-like foliage, it is almost certainly a conifer. If a tree has wide flat leaves and doesn’t look like a conifer or a palm, it’s very likely to be a broadleaf. (Palms have their own world that we will come back to.)

Conifers and broadleaves are in competition in many habitats and structural differences determine which group will succeed. The basic rule is that conifers are tougher: They can survive in many situations where broadleaves struggle. Evergreen conifers can photosynthesize all year round, even at very low levels, which means they do better than broadleaves in zones where the summers are cool and the sun is low. The farther from the equator we travel, the weaker the sun and the more likely it is that conifers will dominate. For example, we can expect to see more conifers in Canada and Scotland than in the US and England.

Conifers have short, thin leaves that are better at conserving water, so they tolerate dry regions better than broadleaves. That is why I saw so many conifers on the dry Spanish mountainside. It is also why we will see a higher ratio of conifers in Mexico and Greece than in the US and England. But we can be more forensic about this.

If a large region has enough rain for broadleaf trees, but we don’t see many, the water may be disappearing somehow. Sandy or rocky soils favor conifers, partly because the water drains away too quickly for broadleaves.

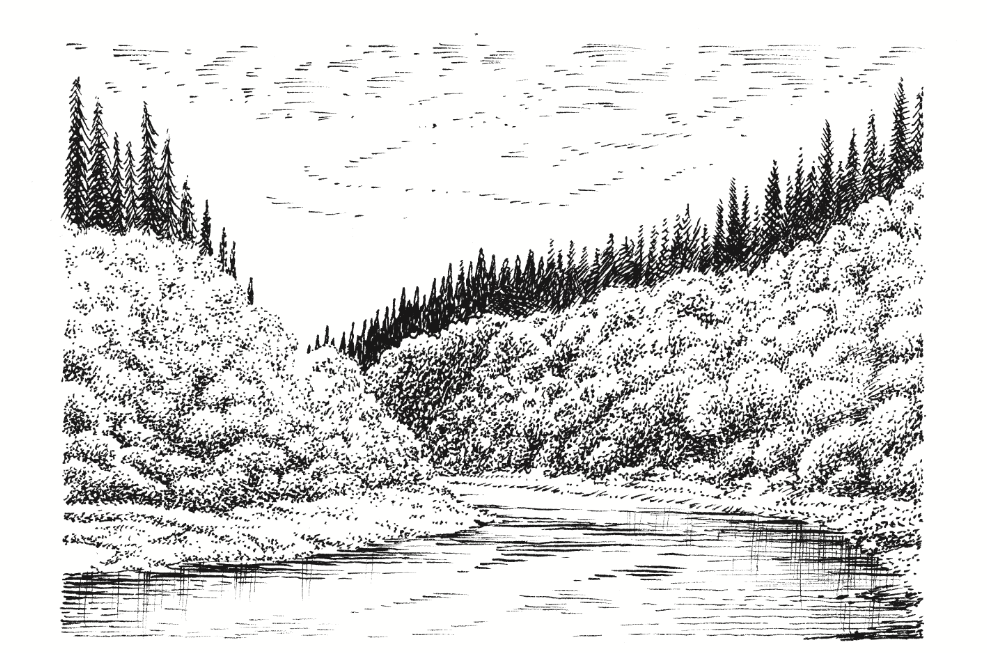

High ground tends to be drier than valleys, which is why you will sometimes find that conifers dominate the hillsides, but broadleaves line the river. Conifers are a darker green than broadleaf trees and this leads to interesting and colorful patterns in the landscape (conifers are mostly evergreens and need thick, tough skins and waxes on their leaves, which makes them appear darker). This is something you will have seen many times, but perhaps never noticed. It’s very satisfying indeed when we understand why a fat ribbon of paler broadleaf trees marks a river’s course. And this satisfaction makes us more likely to look for and spot it. We don’t just see dark green and light green woodland, we understand it is a sign: We know the meaning of the color change and our brain likes that, rewarding us with the pleasant sensation that neuroscientists call dopamine, but we know sounds like “Ah!”

Plants have sap that carries water and nutrients from their roots to their higher parts, but the way this happens is widely misunderstood. The tree loses water from its leaves to the atmosphere through a process called transpiration. This leads to lower pressure in the vessels in the leaves higher up than in those at the bottom of the tree. The sap isn’t pushed from below but is pulled toward the top of the tree by the lower pressure there. In kind climates this is a stable system, but it is delicate, and all plants have some vulnerability to freezing temperatures.

Broadleaves by the River, Conifers on Higher, Drier Ground

Even if a plant survives freezing, the process of thawing can introduce bubbles or “cavitations” into its vessels, which then block the pipes. Broadleaf trees have broad, open vessels that transport sap quickly and efficiently, but these larger vessels are particularly vulnerable to freezing. Conifers transport water from their roots using narrower structures called tracheids that are more resistant to cold temperatures (because the smaller bubbles quickly redissolve). If we look up from the bottom of a mountain, we can see the zone where broadleaves give way to conifers. It is never a perfectly straight line, but above that band broadleaves find it increasingly hard to survive and conifers outcompete them.

If a moist region stays warm all year, removing the risk of frozen sap, broadleaves are likely to do better than conifers. We see a lot more broadleaf trees than conifers in the tropics.

If you’re wondering why all trees didn’t evolve with the freeze-thaw resistant vessels that conifers have, the answers lie, as they so often do with evolution, in efficiency and survival. Broadleaves have a more efficient system, so they do very well if they can survive. But, as the saying goes, you’ve got to be in it to win it. Conifers are the tough but inefficient 4x4s of the road; broadleaves are the modern road car—much more efficient, but falls to pieces on tough terrain.

There’s a couple of fun exceptions to the freezing vessel rule. Birch and maple are broadleaf trees that have devised an ingenious method for dealing with the problems created by frozen sap. They create positive pressure in their narrow vessels, which means they pump sap upward. This gets rid of any bubbles caused by freezing, effectively clearing the pipes in spring. It is how these species survive much farther north than we would expect. The boreal forests of Russia are a good example: They include many conifers, but large areas of birches, too. The positive pressure means these trees have sap that flows out of any cuts in the bark, making it easy to harvest and giving us birch and maple syrups.

Every time we notice broadleaves give way to conifers, we can assume that the environment has become tougher and ask ourselves how and why. The answer is likely to be temperature, soils, water, or a combination, and is part of the map the trees give us.

Spotting this change also shines a light on the psychology of perception. Ask someone to describe a landscape and they may include the word “trees” and not register the change in the woods before their eyes; ask the same person if there are different trees in that same landscape and suddenly the shift from broadleaves to conifers screams out. We have an extraordinary level of control over what we notice, but it is a choice: Nobody is standing next to us to ask these questions.

___________________________

For more, pre-order How to Read a Tree and check out Tristan’s Natural Navigator series, which walks us through the way he sees signs and patterns in the wild that most people overlook. And, see our Summer 2023 catalog for exciting, upcoming titles!