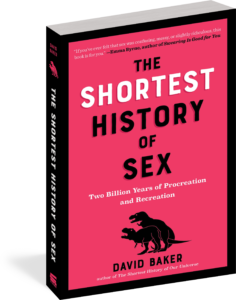

Embarking on a seductive journey through the ages of human sexuality, The Shortest History of Sex promises to unwrap the mysteries of our intimate past, present, and the enticing potential that lies ahead. This narrative spans two billion years of sexual evolution, from microbial rendezvous to the contemporary realms of Tinder and sexbots. With acuity, humor, and a profound respect for the diverse tapestry of human experience, this book weaves a love story of our own existence.

In this Valentine’s Day special, delve into a tantalizing excerpt from the book, offering a passionate glimpse into the present state of human sexuality and daring to peer into the enigmatic future that awaits. Join us as we navigate the coitus chronicles, guided by the wit and wisdom of The Shortest History of Sex.

The Future of Sex

The Present and Beyond

The tremendous revolutions in human sexuality in the past half century have utterly changed sex and romance for Homo sapiens. This change has happened so rapidly it is difficult to predict with any degree of certainty the long-term effects, or how we might be conducting our love lives in a century or two, once the dust settles. Our situation is unprecedented: we don’t see anything like it in nature, of course, and there is no precursor for it in 315,000 years of human history.

For one thing, the existential dependence human beings had on monogamy and marriage in the foraging and agrarian eras has been utterly swept away. In the modern era, individual survival does not depend on family clans, foraging territory, or farmland. And the survival of children does not depend on such things either. Most of the agrarian laws (particularly the most harsh and draconian ones) compelling men and women to stay together in marriages have also been cast aside. All that remains is our somewhat patchy evolutionary predisposition toward monogamy.

For another thing, the substantial liberalization of attitudes toward sex in the developed world means that people can pursue sex and relationships in a multitude of ways, with minimal societal repercussions. As a result, the sway that culture held over sex for the entire existence of Homo sapiens has been decidedly loosened. Want to get married and have kids? Fine. Want to stay single your whole life? Fine. Want to live in a polyandrous commune? Fine, as well. Want to fall in love with an inanimate object such as the Eiffel Tower or develop romantic feelings for an AI personality on your phone? Excellent. Want to have a marathon of promiscuous sex with several hundred partners within the span of a few years? Have at it. Don’t want to start trying for kids until your forties? We’ve got an IVF doctor on standby. Want to spend a third of your income on a domme who calls you a loser and laughs at the size of your penis? Go nuts. Short of committing a felony or violating the consent of another person, there’s very little currently in the developed world that one can’t do.

In a sense, the liberalization of attitudes toward sex has released human sexuality from the grip of culture, returning us to a more evolutionary set of sexual dynamics. While social norms and prejudices still exist, virtually none have the same power to dictate how individuals should live their lives as they did in the agrarian period. We live in a time when the only powerful drivers of a person’s desire to pursue sex and romance are the gradually evolved instincts that we covered in the first two parts of this book, and the unconventional psychology and kinks that result from them. Nurture has ceased to impede the sexual impulses of nature. Most people are still driven by their 1.9-million-year-old monogamous instincts, but with the crossed wires and conflicting evolutionary baggage that stretches back two billion years to the first single cells that exchanged DNA. As one might expect, this can have rather chaotic, unexpected, and at times rather immiserating results. While sexual freedoms are greater than ever, we paradoxically find ourselves in an era where loneliness is at an all-time high and personal happiness is at its lowest ebb.

Lonely Hearts and Calloused Hands

While personal happiness is highly contextual and subjective, and based on the individual, at the largest scale there have been a number of growing trends that we should track. Between 1950 and 1970, the number of Western middle-class women who were having premarital sex increased from approximately 45 percent to 75 percent. Between 1970 and 2020, that number increased again to an estimated 85 to 90 percent (the inverse of habits in 1900). The remaining women were in traditionalist religious communities (9 to 14 percent) or secular cases (around 1 percent). The average marriage age has increased to thirty-two for men and twenty-nine for women, with the marriage rate being lower than at pretty much any time in human history. Couples now date for an average of two to five years before marrying, most of them citing either reservations about the marriage contract (mostly men) or not yet being in a financial position to get married (largely due to the general stagnation of wages behind prices since the 1970s). Still more couples question the value of marriage altogether beyond the possible tax benefits, child protections, and inheritance regulations. In 1970, 0.5 percent of the population in the developed world under forty years old were unmarried cohabiting couples; in 2020, that number had increased to 15 percent.

Meanwhile, the number of single people in the developed world doubled between 1960 and 1970, and today roughly 40 percent of adults in the developed world are neither married nor cohabiting with a romantic partner. In 2019, an average of 45 percent of these singles under the age of forty reported that they were not looking for a committed relationship, with roughly equal numbers for men and women. An estimated 20 to 25 percent of millennials are projected to never get married in their lifetimes, and that number is expected to be even higher for Generation Z. Such is the patchiness of the monogamous instinct when left mostly to itself.

As a result of these trends, millennials and Generation Z are less sexually active than previous generations, with one study finding that rates of casual sex dropped by 14 percent between 2007 and 2017. In that same period, the number of people under thirty reporting no sex in the past year almost doubled. One reason is the sharp decline of in-person socialization among younger people, displaced by heavy use of social media, reducing the number of circumstances where spontaneous throes of passion can arise. Another reason is the decline of in-person flirtation and the growing use of internet dating, which tends to be more selective and exclusionary than hooking up at a club or bar. But the reason that has received the most attention is the rise of free pornographic content online, substituting for real-life sexual encounters.

The exponential growth of pornography on the internet has been staggering. There is now a record amount of online content with which to achieve sexual gratification, even compared to ten years ago. Back then, porn was already a larger industry than Hollywood movies or video games, and most pornography was still produced by production companies, many of them with sketchy business practices.

Increasingly, new independent creators (and even veteran porn stars) are swerving the studio system and uploading content directly onto subscription-based platforms such as OnlyFans. The independent porn market is so saturated that making a living from it can be extremely difficult. Nevertheless, as a result of the side hustle on independent platforms, and the spike of independent content creation during the pandemic, there are now more women making pornography today than at any point in human history (with the specter of coercion reduced but not eliminated).

Meanwhile, an increasing number of men (an estimated two in five) have begun using social media as a masturbatory aide. This trend started with Facebook in the late 2000s: men would send a friend request to a person (whether they knew them or not) in order to masturbate to their photos. Things escalated from 2014 onward with Instagram, where sending a follow request is often not required, effectively turning public female accounts and modeling photos into de facto softcore pornography. A 2019 statistical sample of followers of celebrity and amateur model accounts, and corresponding analysis of what other accounts these followers also followed, revealed that an estimated 31 percent of famous female celebrity accounts and up to 63 percent of amateur model accounts are followed by men likely using Instagram for masturbatory purposes rather than for celebrity gossip, makeup tips, or to see advertisements for clothes or coconut water. There is strong indication that the proportion of softcore masturbators is even higher on TikTok. Reciprocally, this has incentivized a wider number of users to post sexually provocative photographs and videos in order to gain followers and thus be offered advertising contracts and other income. Presumably, despite the fact that a large portion of followers are there just to masturbate rather than be a target demographic for fashion and lifestyle products, merchandisers are still making back the money from their ad budgets. Otherwise, the bubble of advertising investment in such social media accounts may one day burst.

Meanwhile, excessive online porn use is causing record levels of erectile dysfunction during real-life sex. According to the Reward Foundation, approximately 24.5 percent of men under 40 now experience difficulties in such situations, up from 2 to 3 percent of men under 40 in the year 2000. Essentially, men are becoming so overstimulated by using pornography when they are sexless that sweet, passionate sex with a woman they are lucky enough to meet is not sustaining their arousal.

When it comes to satisfying emotional rather than just sexual needs, both men and women are increasingly turning to AI apps and chatbots for daily conversation and intimacy. While early chatbots from ten to twenty years ago were extremely limited, AI such as the Replika app (with millions of downloads) can increasingly learn to carry on conversations and get quite nuanced. Nevertheless, the technology has not yet reached the point where an AI can comprehend every twist and turn of a conversation. But within another decade or so, it is likely a conversation with an AI companion online will be almost indistinguishable from texting with another person.