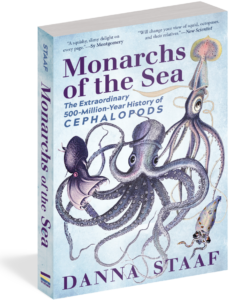

Monarchs of the Sea publishes today! Whether you’re new to the world of cephalopods or are a full-fledged fan, there’s something fascinating for everyone to learn in this deep dive (no pun intended) by marine biologist Danna Staaf. Hailed as “surprising, smart, and weird in the very coolest sense of the word” (Sy Montgomery, New York Times–bestselling author of The Soul of an Octopus), you won’t want to miss out on the history of these otherwordly creatures that once ruled the deep. Check out our Q&A with Danna Staaf below, and don’t forget to enter our giveaway with OctoNation® on Instagram! Monarchs of the Sea is available wherever books are sold.

Monarchs of the Sea publishes today! Whether you’re new to the world of cephalopods or are a full-fledged fan, there’s something fascinating for everyone to learn in this deep dive (no pun intended) by marine biologist Danna Staaf. Hailed as “surprising, smart, and weird in the very coolest sense of the word” (Sy Montgomery, New York Times–bestselling author of The Soul of an Octopus), you won’t want to miss out on the history of these otherwordly creatures that once ruled the deep. Check out our Q&A with Danna Staaf below, and don’t forget to enter our giveaway with OctoNation® on Instagram! Monarchs of the Sea is available wherever books are sold.

***

Q: What got you interested in cephalopods?

Danna Staaf: My family took a trip to the Monterey Bay Aquarium when I was about ten, and I spent most of our visit in front of the octopus tank, mesmerized. I fell in love. When we got home I hounded my parents until they let me keep a pet octopus, and then I learned to scuba dive and it just snowballed from there.

Q: What is your favorite living cephalopod?

DS: Vampire squid. Their scientific name translates as “vampire squid from hell” and yet they are really shy, gentle creatures. We only learned what they eat in 2012—it’s poop and bits of dead animals. They just catch the stuff that falls down to them from higher up in the ocean. They’re the only cephalopod that does this. Plus, they shoot glowing mucus instead of ink, and that’s just rad.

Q: Favorite extinct cephalopod?

DS: Probably the heteromorph ammonites. Their name means “other shapes” and some of their shells were really bizarre, like paperclips and soft-serve ice cream. Especially one called Nipponites—its shell literally grew in a knot. I’m dying to know what was advantageous about that, and hopeful that paleontologists will figure it out one day

Q: Why should anyone else care about cephalopods?

DS: From a practical point of view, they’re super important to the oceans we know and love. They’re a major source of food for most large sea creatures—seals, dolphins, whales, sharks, even seabirds. They also support some of the fastest-growing fisheries to feed humans. Our fates are definitely entangled. They can teach us more than any other group of animals about the evolution of complex brains. And beyond all that, they’re beautiful and astonishing and unlike anything else on the planet. I don’t think anyone can watch videos of an octopus’s instant camouflage, or a cuttlefish’s hypnotic patterns, without feeling just a touch of awe.

Q: Are there any fun facts about cephalopods that you didn’t get to include in Monarchs of the Sea that you’d like readers to know?

DS: Some deep-sea squid fill their own transparent bodies with ink and no one knows why! Vampire squid are born with a pair of “baby fins” that they use to swim before growing their “adult fins.” For a little while, they have four fins, then the baby fins are resorbed back into their body. Larvae of another group of squid, the Chiroteuthidae, grow an incredibly long and bizarre “tail” that they lose as they grow up. Why? It’s still pretty mysterious!

Q: In the book, you discuss the logistics and benefits of adopting cephalopods as model organisms for research. If any, what are the ethical considerations involved with the use of cephalopods as model organisms? Are they outweighed by the potential benefits?

DS: Scientists use the three r’s to guide the ethics of animal research: replace, reduce, and refine. Replacement means: can the research questions be answered without using animals, say, with an experiment on isolated cells instead of whole organisms? Reduction means using no more animals than necessary to obtain results, and maximizing the data obtained from each experiment. Refinement refers to humane treatment, the conditions in which the animals are kept, using appropriate anesthetic and euthanasia when necessary. These are all as applicable to cephalopods as to any other animal, and I think one good thing about developing new model organisms is that ethical considerations can be front lined from the beginning. So far, I’ve seen that the scientists working on developing cephalopod models really prioritize the animals’ welfare, and that’s encouraging.

Q: What burning question do you have about cephalopods—past, present, or future—that you most hope research answers next?

DS: It’s hard to pick just one! I think I’d most like to know about social behaviors. For a long time we’ve had this idea that octopuses are intelligent, but solitary. Recently, there have been more discoveries of groups of octopuses living together (Octopolis, Octatlantis, octopus mothers all brooding their eggs together in the deep sea) and we’re still fumbling around at the very beginning of understanding why and how they congregate like this.

We’ve known for longer that cuttlefish and squid gather in groups, but we’re also still very much in the dark in terms of grasping the complexity of their interactions with each other, whether and how much they are truly communicating. We only just learned that Humboldt squid, for example, use bioluminescence as part of their communication. I bet there’s going to be a lot more exciting stuff in this field!

Q: What’s your next project?

DS: I’m writing a middle-grade biography of the pioneering female marine biologist Jeanne Villepreux-Power. She worked in Sicily in the 1830’s, where she invented the first modern aquariums, then used them to solve the mystery of the argonaut octopuses. Argonauts are the only octopuses that grow their own shells, and Jeanne figured out how they do it.

Q: What advice do you have for someone hoping to become a cephalopod scientist?

DS: To search broadly for opportunities, try lots of different things, and think hard about what kind of work you want to do. There are academic scientists, government scientists, scientists who work at nonprofits, aquariums, museums, zoos. I spent six years in academic science before becoming a science writer, a job I’m much happier with. Also remember that it’s worth taking research opportunities that aren’t with cephalopods at all, to gain skills, make money, and find out if you like that kind of work.

***

Interview with Danna Staaf, author of Monarchs of the Sea: The Extraordinary 500-Million-Year History of Cephalopods (The Experiment, September 2020)

theexperimentpublishing.com