Today marks a milestone anniversary for Earth Day—fifty years! It’s an important moment that not only honors our planet, but forces us to consider its future. With issues like climate change, sustainability, and pollution becoming more widespread, understanding the history of environmental conservation and protection is more important than ever.

When you think of environmental protection, our national park system is sure to come to mind. After all, what could be better for the environment than sanctuaries that preserve nature for thousands of species of plants and animals?

But the “correct” way to maintain nature in our parks has never been straightforward. Ecologists, politicians, environmentalists, and activists have debated this since before our first national park, Yellowstone, was even created. Here are few interesting facts that you might not know about Yellowstone:

- Founded in 1872, Yellowstone’s 2.2 million-acre-plot is the first national park in the world.

- Yellowstone sits atop an active supervolcano, which is made up of a mass of semi-molten rock that is 270 miles high.

- Yellowstone is home to at least 67 species of mammals—including wolves, bison, and elk—and 285 species of birds.

- By excavating some of the estimated 80,000 archeological sites in Yellowstone, we know that Ancient Americans lived there as early as 11,000 years ago, but Native American populations were all but wiped out by disease and other effects of western expansion by the mid-nineteenth century.

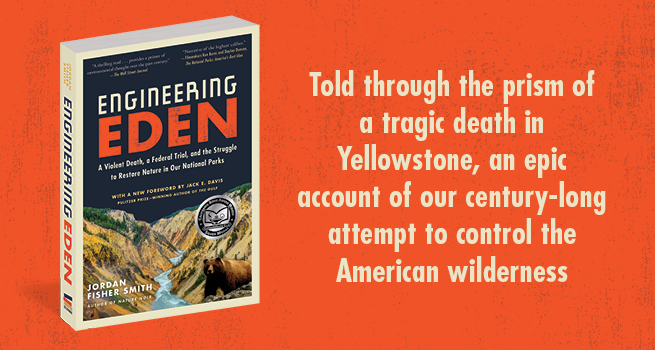

In Engineering Eden, author and former park ranger Jordan Fisher Smith crafts an epic, emotionally wrenching account of the fraught civil trial that ensued after the death of a young man in Yellowstone National Park. This trial not only determined the future of the park, but the future of all of America’s national parks, and their conservation and preservation for future generations. Read on for an excerpt from the Engineering Eden, and be sure to grab your copy of the book, available now!

***

The search for truth at the heart of this book—a story of tragedy and conflict and the laden relationship between humanity and nature—might begin with one of the old refuse dumps at Yellowstone National Park.

Or it might launch from the basic human proclivity to be in control. A similar tendency exists across species: A wolf pack, for example, will wage war against another pack to defend or expand its territory. The difference for humans is that dominance is driven not simply by an instinct for survival, but also from vanity and the desire for wealth and leisure. Along with our immediate world, humans seek to control the larger one—everything that’s in it, and the forces that shape it—the forces of nature. We redesign, alter, and even reinvent nature. We engineer it, as the title of Jordan Fisher Smith’s perceptive book suggests. Or we try to—sometimes innocently, sometimes arrogantly—and fail, even when we think we’ve succeeded.

The central subject of this book—what happened in Yellowstone National Park in the 1960s and 70s among visitors, scientists, bureaucrats, and bears—offers an example of how manhandling nature can go awry. From its founding, the United States has visualized its identity and destiny in the unbounded physicality of the continent, the vast stretches of land—and all upon it—of which the country took possession. National parks are living museums holding that vision, paying tribute to the country’s national and natural heritages. They are an original idea, some say America’s best. Expressed less romantically, they are an invented ideal, patented in the USA, and embossed with the imprint of civilization.

Americans created Yellowstone and its later siblings to meet their expectation of how the raw and unembellished world should look or be improved, yet all the while believed they were sanctifying nature. What they sanctified were select outstanding features of the nation’s native endowments—such as a dazzling waterfall or picturesque valley. They created parks as showpieces that said their young nation was gifted with rarified beauty and wealth in nature that set it apart from other countries. They created them to provide an escape—from the grime and grind of an urbanizing and industrializing nation—to a garden spot that renewed the spirit and entertained the senses. Although policy emphasized natural features, parks were among the nation’s first tourist traps, and so succumbed to a degree of artificiality. The poisonous, prickly, and predacious had to be eradicated, and the unsightly tidied up or eliminated. Managing wildlife was imperative. Killer animals were trapped and shot to ensure that pastoral species, such as bison and deer, moved in diorama fashion across a serene landscape. Horror would otherwise prevail for seekers of bucolic bliss, if exposed to wolves or mountain lions taking down an elk.

Bears fell between acceptable and unacceptable wildlife. They were dangerous but storybook cute, and a major attraction. They were a spectacle really, called to entertain at the open dumps or, in the case of Yellowstone, on a makeshift stage surrounded by theater-like bleachers and excited audiences, where according to script they scrounged for food leftovers from the parks’ hotels. The final cue directed them to exit and return to the wild, peacefully, until the next performance.

A certain naivete lay behind the popularity of these exhibitions: Apart from our cultural attachment to parks, they are ecologically complicated places; and even with everything that science knows today, nature retains its mysteries. Americans knew far less about the environment in 1872, when they established Yellowstone as the country’s first officially designated national park. Turning a natural place into a cultural one created unexpected consequences, a messiness that experts tried to ignore or work around.

Yellowstone began as a noble experiment in engineering what was supposed to be a kind of Eden. There was no precedent for what Americans were doing, no example to follow. As happens with many experiments, this one encountered setbacks, too often predetermined by ignorance, indifference, and society’s priorities. Technological and economic growth took precedence over all other developments in American culture, as the environment rendered exploitable commodities that enriched and empowered the nation. Nature became property and produce, a storehouse of marketable assets—so-called “natural resources”—that were God’s gifts to humankind. Although a preservationist creed—to wit, leave nature wild—formed within the early conservation movement, the competing creed, the one that most influenced federal policy, was utilitarian in essence and people-centered in practice: Preserve the forest to protect the watershed that filled the flowing river that moved the cargo barges. An exception to this pecuniary logic existed in the reverence for scenic wonders within the parks. Still, the pervading utilitarianism of resort hotels and drive-in campgrounds cheapened sublime experiences.

In the early years, natural science offered no resistance to this trend. Any significant comprehension of the interconnectedness of life was beyond those biologists. They had yet to study how species interacted with their environment or maintained balances in a given system, such as the food web, of an ecological community. Park managers were not only trying to control nature—they were doing so in the dark. Breakthroughs in science that might have made a difference in preserving natural conditions rarely got a hearing among policymakers, whose agendas underscored increasing visitor traffic.

By the 1920s and 30s, biologists had begun talking—mainly among themselves—about connections and balances, and rethinking the importance of the presumably undesirable, such as wildfires and predators. New insight frequently came by way of stumbling on it, as when devastation to native flora, and biodiversity from herbivore population explosions, revealed the fallacy of predator control. Trying to understand unexpected calamities of intrusion and manipulation advanced the discipline of ecological science as a legitimate field of study, which the American academy had cavalierly ignored until mid-century. By then, favored disciplines were thrusting the country into both the nuclear and synthetic age while reversing evolution. Against this canonical thrust, studies in ecology (and ruined ecosystems) ignited a revolution in questioning traditional relationships with nature.

Jordan Fisher Smith explores this transition in depth, as a prelude to the pivotal moment when the park service decided to put nature back into its parks—to bring America’s best idea closer to the true ideal. Among the many strengths of his book are the big questions he asks and the contexts he fleshes out, taking readers beyond Yellowstone and bears. Engineering Eden is the campfire talk around which every American should gather, and Smith is the science teacher we all wanted in school, skilled at translating the complex into the comprehensible. Whether describing the grand canvas or a picture postcard, he is a virtuoso of landscape and language, reverential in his feeling for nature and the written word. After more than two decades as a park ranger, he knows the terrain: the winding wooded trails of parkland, and the twisted paneled corridors of park-service bureaucracy. There was no less drama in one than the other, no less conflict between people and nature than among people themselves.

Biologists, lawyers, and wildlife advocates became entangled in discord: They collided over how to shut down the dumps and the carnival feeding, and how to stop bears from invading campsites for lost offerings—endangering, indeed mauling, visitors. To break bears of doing exactly what humans had conditioned them to do, some experts supported a cold-turkey approach—and others, a gradual one. Some called for intervention (give nature a nudge), others rabidly opposed it (let nature work it out). The assembly of characters in the book is large, but here again Smith is in command as a writer, keeping them properly sorted, showing each as a multidimensional individual. Their conflict raised questions of professional reputation, park policy, the future for wildlife management, and even the meaning of nature. Egos flared, lawsuits were filed, lives were lost. The truth is, no one could be certain of the right approach. At the time, scientists were still working out basic ideas in ecology; they could not expect to know the correct methods for restoring an ecosystem, and much less for preventing human-made tragedies that continue to threaten the lives of both Homo sapiens and Ursidae.

Smith’s object lesson is focused on how the past might guide us through twenty-first-century challenges, bigger than bears and parks. Facing climate change, rising seas, and the Sixth Extinction, humans can either work with nature or take their last futile stand against it.

Ultimately, Smith doesn’t begin his search for truth with the human proclivity to control nature or with bears unceremoniously gorging at the dump. A master at crafting narrative, Smith opens with a young farmer—his body wracked with the ache of hard work—who sets out from his home in northern Alabama to replenish his spirit and body at Yellowstone. In these pages, readers join Harry Eugene Walker as he enters a realm of beauty and tragedy; they emerge potentially wiser about humanity’s journey ahead.

***