For many of us, every single day is a day to love and dote on our pets—but did you know that today is National Love Your Pet Day? The holiday encourages us to pamper our pets, giving them extra attention, and focus on the ways they make our lives better. (As if we don’t already spoil our pets every single day.)

For many of us, every single day is a day to love and dote on our pets—but did you know that today is National Love Your Pet Day? The holiday encourages us to pamper our pets, giving them extra attention, and focus on the ways they make our lives better. (As if we don’t already spoil our pets every single day.)

In honor of #NationalLoveYourPetDay this month (and for the dog lovers out there), we have just the book for you: Making Dogs Happy! With this comprehensive guide written by experts Paul McGreevy and Melissa Starling, you’ll learn to see the world as your dog does—full of goals to pursue, resources to guard, and stressors to avoid. Using that knowledge, you’ll be able to communicate with (and train) your dog so that they’re the happiest hound on the block. Read on for an excerpt from Making Dogs Happy, available now. And be sure to tweet at @experimentbooks with a photo of your pet!

***

THERE ARE MANY PATHS TO DOG HAPPINESS BUT ALL OF THEM START WITH GOALS, AND GETTING CLOSER TO THEM.

Scientists working on rewards and emotions are beginning to suggest a simple, binary nature to positive and negative emotional states and how animals navigate their world to find rewards and avoid discomfort. They suggest that positive emotional states are inherently tied to getting closer to obtaining goals, while negative emotional states are inherently tied to getting further away from obtaining goals. For the sake of a dog-focused example, any time a dog is awake the world holds opportunities and there are a variety of goals the dog will find attractive. These goals depend on both the dog’s current biological needs and the outcomes that become likely from moment to moment. The best dog owners are well aware of this and monitor their dog closely for patterns of behavior that will tell them what is important to their dog. This is an example of dogmanship and explains why, regardless of whether they ever intended to be, these owners are lifelong students of dog behavior.

Scientists working on rewards and emotions are beginning to suggest a simple, binary nature to positive and negative emotional states and how animals navigate their world to find rewards and avoid discomfort. They suggest that positive emotional states are inherently tied to getting closer to obtaining goals, while negative emotional states are inherently tied to getting further away from obtaining goals. For the sake of a dog-focused example, any time a dog is awake the world holds opportunities and there are a variety of goals the dog will find attractive. These goals depend on both the dog’s current biological needs and the outcomes that become likely from moment to moment. The best dog owners are well aware of this and monitor their dog closely for patterns of behavior that will tell them what is important to their dog. This is an example of dogmanship and explains why, regardless of whether they ever intended to be, these owners are lifelong students of dog behavior.

It’s a dog’s life, goal by goal

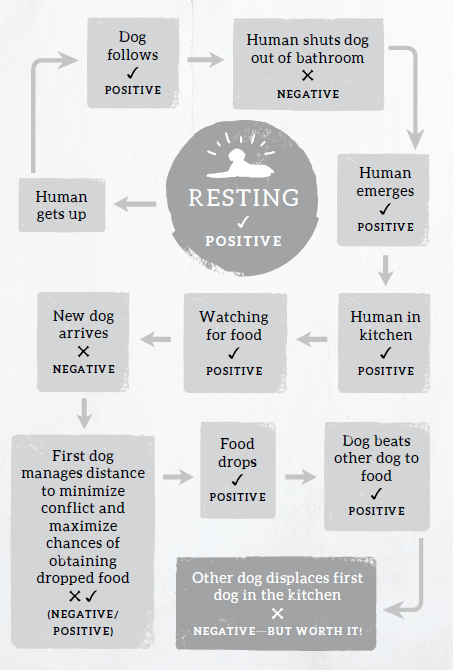

A dog’s goals can vary wildly, just as human goals can. Let’s take, for example, a dog in a multi-dog household, who is fed and walked in the morning. It is easy to imagine how her emotional state can change in just a few hours. We can map that out in a simple diagram that follows her goals and whether or not they are achieved.

When it is approaching lunchtime and the dog is well fed, and she has spent the early part of the morning (when she is most active) playing, running, and exploring—and she has relieved herself, and no one in the household is doing anything of particular interest— her primary goal might be to simply rest comfortably. This is easily achieved and so she is content.

Perhaps she chooses to rest where she can monitor the household and be instantly aware of any interesting activity the moment it begins, such as her human heading to the bathroom. In that instant, her goal might switch from resting to trying to reach the bathroom door before it closes, so she can participate in bathroom-visiting with her human; her emotional state shifts, depending on whether she is successful or not. Maybe her human stood up from a desk because it’s lunchtime, and when the human starts to move about the kitchen, her goal splits between participating in human activities in the kitchen and obtaining any food that falls onto the floor. Both these goals are easily met simultaneously by being in the kitchen.

Perhaps the sound of busyness in the kitchen entices another dog to come in, and now our first dog’s goals split again to participating in human activities, obtaining any food that drops on the floor, and maintaining a safe distance from the second dog to avoid being forcefully displaced from the kitchen. Imagine how both dogs’ emotional states might fluctuate as they navigate this daily chain of events.

You can see that, at any one moment, our first dog is not necessarily happy or unhappy. She might or might not have achieved her goal, and it might be impossible to achieve all her goals without compromises. It might not even be clear if she is getting closer or further from her goal at any one moment. Some steps are ambiguous. In some households, going to the kitchen when food is being prepared is a fair bet (but not a sure bet) for snatching food off the floor. The arrival of the competitor dog introduces conflicting goals. Our original dog now has to weigh closeness to the potential food drop zone against the risk of aggressive behavior from the other dog. Our first dog might move further away from the food preparation area, which means being further from the goal of obtaining fallen food, but closer to the goal of avoiding aggressive behavior from the other dog.

So the first step towards making dogs happy is to identify their goals. Food, water, fun, company, safety and comfort seem to be important resources for dogs, regardless of breed or age, and obtaining resources is a common goal for all animals. However, dogs do have individual preferences that can be strong and, as we have just seen, what they want can change depending on time of day, degree of hunger, competing stimuli in the environment, their sense of safety and their energy level. One way we can identify a dog’s goals is to use learning theory—in particular, instrumental conditioning.

Instant gratification

Early psychologists, such as Edward Thorndike and B. F. Skinner, discovered that animals are more likely to repeat behaviors that are immediately followed by a reward, such as food. The food therefore strengthens or reinforces the behavior and can itself be called a “reinforcer.” This kind of learning is generally called “instrumental conditioning,” because the response is instrumental in making the reinforcer appear (or in allowing the animal to avoid a noxious stimulus). Those who are familiar with psychology or animal training may be more familiar with the term “operant conditioning,” which is a term Skinner favored to describe the trial-and-error learning that occurs when animals learn a new task by very simple problem-solving. The animal learns from the consequences of their attempts to acquire a reinforcer (reinforcement) or to avoid an unpleasant outcome (punishment). The signals that tell the animal when those consequences apply are known as “antecedents.” For example, your dog might sit when you ask him to, but only when you have food in your hand. This is because the presence of food is the antecedent that tells him he will get food if he sits rather than you asking him to sit being the antecedent that tells him he will get food if he sits. This is a common training error. The solution is to ask him to sit when you don’t have food in your hand, and then grab some from nearby (for example, your pocket) to give him when he does sit.

Understanding how rewards can reinforce behaviors is a powerful tool for identifying our dog’s current goals. Whenever a dog starts performing a behavior more often, with more intensity, or for longer, we can ask ourselves what is reinforcing this behavior? What is the dog achieving with this behavior? Be warned: the answer is not always obvious! In some cases, we can see a clear relationship . . . Your dog rests his chin on your knee because you typically respond by stroking his head and fussing over how cute he is. He doesn’t know that the combination of floppy cheeks and jowls over your knee and lifting his brows so he can gaze at you without moving his head is a near lethal concoction of heart-melting adorableness that few dog lovers can resist. He simply knows it leads to an affectionate human, and if he does more of it we can be sure that he enjoys the affectionate head stroking and fussing.

Understanding how rewards can reinforce behaviors is a powerful tool for identifying our dog’s current goals. Whenever a dog starts performing a behavior more often, with more intensity, or for longer, we can ask ourselves what is reinforcing this behavior? What is the dog achieving with this behavior? Be warned: the answer is not always obvious! In some cases, we can see a clear relationship . . . Your dog rests his chin on your knee because you typically respond by stroking his head and fussing over how cute he is. He doesn’t know that the combination of floppy cheeks and jowls over your knee and lifting his brows so he can gaze at you without moving his head is a near lethal concoction of heart-melting adorableness that few dog lovers can resist. He simply knows it leads to an affectionate human, and if he does more of it we can be sure that he enjoys the affectionate head stroking and fussing.

Using this framework, you can test your assumptions about your dog’s preferences. If you suspect your dog likes something, start delivering it consistently and immediately after your dog has engaged in a particular behavior. If the behavior meets one or more of those criteria for being reinforced—it increases in frequency, duration, or intensity—then you are spot on. This is a worthwhile exercise, because sometimes we are wrong about what our dogs like. Sometimes dogs have unintuitive ways of telling us when they don’t like something (we will cover this in greater detail later) and not every dog follows the same patterns of behavior. Sometimes the only way to decipher a dog’s goal is to make a prediction and test it. Again, the best dog owners are lifelong students of dog behavior.

Fortunately, dogs are expressive creatures and dog owners often have a good idea what their dogs like because of the way they respond to signals. Dogs that start to race around the house when someone says “walk” are showing us with their enormous increase in unnecessary activity that they are very enthusiastic about what generally happens after someone says “walk.” The decisions dogs make when two good things are available and they have to choose between them tells us about their preferences. The crinkle of a bag of treats being opened is often enough to convince a dog to come away from something they are barking at, whereas the promise of an ear scratch might not be enough to lure them.

***

Excerpt from Making Dogs Happy: Guide To How They Think, What They Do (and Don’t) Want, and Getting to “Good Dog!” Behavior. Copyright © 2018, 2019 by Melissa Starling and Paul McGreevy