In his previous books, master outdoorsman Tristan Gooley shared with readers the tips and tricks he’s cultivated over years of his own experience as an outdoorsman. In The Nature Instinct, other leading experts weigh in along with Gooley, to show us how they developed a “sixth sense” that allows them to subconsciously understand the inner workings of our natural world.

In his previous books, master outdoorsman Tristan Gooley shared with readers the tips and tricks he’s cultivated over years of his own experience as an outdoorsman. In The Nature Instinct, other leading experts weigh in along with Gooley, to show us how they developed a “sixth sense” that allows them to subconsciously understand the inner workings of our natural world.

In the following excerpt from the book, Gooley shows us this “sixth sense” at work, and gives insight into how we might unlock this ability ourselves.

Sit on a patch of earth for ten minutes, and all manner of motion will appear. Leaves oscillate in the breeze, sun flecks roll over the undergrowth, birds fly by, insects introduce them elves through flight and wriggling, while ants or beetles may parade. If we choose to look, we will also see the world of the still, the shapes of trees, the colors of earth and flowers, the shades of leaves. When we stand up and walk briskly for ten minutes, our eyes may miss all but the bigger beasts and brightest butterflies. But our brain is busy noticing the things we think we miss.

I drove west along a road that was the blackest of wet tarmacs. There were hedges on either side that didn’t register except as a speckled brown blur with the odd white burst of old man’s beard, a type of lichen. The bare trees loomed as silhouettes, then raced by. My mind was on my destination, a mundane meeting an hour away, ready to gobble up my morning, then disappear from diary and memory. And then I felt it. I sensed south.

A few years ago, there was a collision between a tree and a star constellation in my head and the world has seemed different ever since. The south I saw on that drive was the result of a shape I have come to know very well. It is called the “tick effect.” Phototropism, the way plant growth is influenced by light, leads to tree branches in the northern hemisphere growing closer to horizontal on the southern side and closer to vertical on the northern side. This creates a recognizable tick, or check mark, shape when the tree is viewed from one side.

I had sensed this shape in a tree by the roadside, one I wasn’t even looking at, while traveling at about 30 mph. And its familiarity gave me the warm fuzzy feeling that comes with recognition of any pattern we know and like. It also gave me an instant sense of direction.

A couple of days later, I was running a course for a small group in southeast England and I led them to an ash tree. I had chosen it from hundreds of others because it was an exemplar of the tick effect. I gathered the group in the perfect spot to give the ideal perspective of the tree, then stood in front of it and pointed out the shape to them. I enjoy these moments, because others do: Something that may have passed unnoticed is highlighted and then it shines out from nature. It becomes surprisingly obvious.

There were nods and smiles. Most of the group saw it straight away, but two people didn’t. I tried again, demonstrating the effect more slowly and deliberately, sketching in the air the silhouetted shape of the branches that made the checkmark. Not a flicker of recognition. During the third attempt, I felt a tinge of irritation—how could those two not see what was plainly in front of their eyes?

I quelled the irritation. There is no point in being a teacher of anything if you can’t find the positive challenge in such situations. I tried another tack. I asked the pair to squint: This can filter out smaller details and help us to spot larger shapes. By the fourth variation, everyone in the group could see the effect. And by the end of the afternoon, one of the two who had struggled to spot it pointed out the effect in a distant tree before anyone else, including me, had noticed it.

Later that day, relaxing with a cup of tea, I tried to empathize with the two who had had difficulty seeing the shape. I thought about how I must once have been unable to detect it—I started noticing it in my late twenties, so before that it must have passed me by. Yet it was now announcing itself, leaping out of the blur to the side of a car I was driving. It was not just the shape that was now so easy for me to see, but its meaning. I was sensing direction from a tree, without even trying. How strange, I thought.

The constellation Orion straddles Earth’s equator. As a consequence, it rises in the east and sets in the west. Also, it’s visible all over the world, which makes it a favorite constellation for natural navigation. I have come to know it very well and have learned to sense direction from Orion without giving it much thought. But for many years I had to think about it. And to get from Orion meaning little to its announcing direction instantly, I must have followed the same paths of recognition that everyone traces with star constellations until something unusual happened.

First, we learn to recognize the pattern of a constellation. This must be why our ancestors concocted constellations; they were almost certainly invented in prehistory to give us something to recognize and help us to make sense of a complex picture. Our brains have evolved to find and recognize patterns, which allows us to impose and then find order in the thousands of stars that are visible at night. A night sky that would otherwise appear random and overwhelming is a collection of patterns we can identify.

The more familiar we become with the constellations, the more comfortable the night sky feels. But it is the recognition of the patterns that is vital. Recently, in an inflatable planetarium in Wales, I was listening to a talk by Martin Griffiths, a professor of astronomy, about the constellations and patterns that the Celts once saw in the night sky. It was a delightful talk but, however fascinating it was culturally, it became uncomfortable on a psychological level. I watched as the professor tore up the ancient patterns I knew and substituted different ones. It almost made me queasy. The telling thing was that none of the stars changed or moved, but he redrew the patterns. A bear mutated into a horse, a scorpion became a beaver. Small details perhaps, but it disrupted my comfort with the night sky. After the talk, I went back across the fields, guided by more familiar patterns.

Once we have learned to recognize a constellation, like Orion, the next step in natural navigation is becoming familiar with its meaning in terms of direction. In the case of Orion, it’s not difficult to get started: Since it rises in the east and sets in the west, if you see it near the horizon you must be looking east or west. If, after half an hour, you notice it has gone up a bit, you’re looking east, and if it has sunk, you’re looking west.

The Orion method is a straightforward way of gauging approximate direction using a pattern in the night sky. I used to do it regularly. I never decided to stop, but it isn’t what I do now. Now when I see Orion, I see direction. I’m not talking about numbers of degrees or words like “east” or “west” popping into my head: Those are labels of direction. I actually see direction. Which, I hope you’ll agree, is a bit odd. But it is something you can see. And you’ll soon be seeing direction in the night sky, but only as one tiny part of a new awareness. More importantly, you’ll be regaining your sense of what’s going on around you outdoors. I’ll give you the nuts and bolts of the Orion method later, but first I’d like to share with you how it fits into the small revolution—perhaps renaissance is a better word, you decide!—in the way we can experience the outdoors.

The San people in the Kalahari desert report experiencing a powerful burning sensation when they are getting close to an animal they are hunting, and Aboriginal peoples of Australia have talked of orienting themselves using a “feeling.” In 1973, when asked how he found his way, Wintinna Mick, an Aboriginal Australian, told the navigator and scholar David Lewis, “I have a feeling . . . Feel in my head. Been in the bush since small. That way is northwest.” Lewis thought he was calculating this using the sun, but Mick was insistent that he was not: “I know this northwest direction not by the sun, but by the map inside my head.”

We know that people who live in indigenous communities in wild places have an awareness of their surroundings that eludes those of us living in an industrialized society. A sense of direction is a small part of this, but by no means the most important.

During the Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, rational thought was prized over the religious faith that had dominated for centuries. Cartesian rationalism and the weights, measures, and machines of the scientific revolution prevailed. Intellectual snobbery ensued, and any suspicion that the heart was being allowed to rule the head was viewed skeptically by the intellectual vanguard of the time. It was a decisive shift and, despite pockets of resistance and a determined fight by Romanticism, it has prevailed to this day. The savage was not noble, just ignorant. The gut was denied its feeling.

It’s not only indigenous communities who have this awareness; animals have it too, of course. Which may explain why this form of thinking has unfortunately been seen as inferior historically, typical of the “lower” beasts and “natives.” What sort of argument could be made in favor of the way tribespeople experience their environment when pitted against a civilization that gave us steam engines and a vaccination against smallpox? How hard is it still to value it from a culture of space travel and the Internet? We have gained so much through a more analytical view of the world, but at what cost?

This is not a new concern. We’ve had a nagging suspicion for centuries that we were becoming cleverer with each passing year, but perhaps not growing any more aware. William Cowper, the eighteenth-century English poet, expressed this in “The Doves”:

Reas’ning at every step he treads,

Man yet mistakes his way,

While meaner things whom instinct leads

Are rarely known to stray.

He knew that as our maps became better, we were losing our deeper understanding of the territory.

Years after pondering tree shapes and my experiences with Orion, I began reading books and papers that I hoped would help me understand what was going on. Thanks to the work of many extraordinary researchers, such as the psychologists Gary Klein, Amos Tversky, and Daniel Kahneman, the mystery was solved. I could suddenly see a path to rediscovering our lost sense of awareness outdoors.

We have two ways of thinking and we need both, because each is excellent at certain things and rubbish at others. Consider this unlikely scenario: You are relaxing at home, watching TV, when a stranger kicks down your door and runs into the room wielding a knife. At this point your brain has performed a lot of assessments of the situation very quickly. You have made decisions about whether to run away, fight back, or stay put. Your pulse has risen, you are perspiring, and your breathing has changed. All of this has taken place automatically. At this point the intruder seizes you, holds the sharp, cold knife against your throat, and whispers in your ear, “A car drives at sixty miles per hour for two hours, then at forty miles per hour for another two hours. How far did it travel? Answer correctly and I’ll let you go. Get it wrong and you’re dead!”

“Uh . . . two hundred miles,” you reply.

They let you go and disappear into the night.

In the space of one surreal minute you have used two different types of thinking. Some psychologists call the two ways of thinking System 1 and System 2. But I’ve found that’s too dry to be memorable and quickly becomes confusing. Daniel Kahneman has better labels: fast and slow, as outlined in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. If we need to compare or calculate things, follow rules, or make deliberate choices, this is “slow” thinking. If we are surprised by a sound, sense anger, feel beauty, or take fright, this is “fast” thinking.

How can we tell one type of thinking from the other? There is no perfect method, but the best clue is that if we can tell we’re thinking about something, it’s conscious thinking. It’s slow. If we react to something “without thinking about it,” then the truth is that we have thought about it, just using the system that we don’t consciously acknowledge. This is fast thinking. When indigenous people show an instant awareness of their surroundings without appearing to think about it, they’re using fast thinking. And I’m convinced that this was a far greater part of all humanity’s outdoor perspective ten thousand years ago and at all times before the first agricultural revolution.

If we imagine there being a sliding scale from fast unconscious thought at one end to slow conscious thought at the other, we can picture our ancestors being closer to the fast end than contemporary indigenous people, and those of us who enjoy the odd Starbucks as being toward the slower end. It is important to stress that this has nothing to do with intelligence; there has been no significant biological change in our brains during the time period. The differences are cultural. Or, put another way, an average human of ten thousand years ago could solve The Times crossword as fast as his or her counterpart today, if they had led the same lifestyle and had the same influences. Ironically, according to eminent historians like Yuval Noah Harari, they probably had more free time than us, so they may have enjoyed the distraction.

Fortunately, there isn’t yet a great wall between us and this experience of the outdoors. It is just that this faculty has shrunk to the point where it is a minor part of our experience. I remember giving a talk in a town in Essex, in southeast England, and staying in a hotel overnight afterward. During breakfast the following morning, I was thinking about the ideas in this book and a very cheery elderly waitress was pouring my tea for me when she said, “Looks like rain.”

We were indoors and, to the best of my knowledge, she had not set foot outside for quite a while. Sure enough, by the end of my breakfast it had begun to rain. Because I was contemplating this book, I asked her how she had known it would rain. She looked pleasantly shocked to have been asked something so strange. But after a short pause, it transpired that there was no mystery: The skies had darkened a little, and this was evident even from the small amount of natural light reaching into a room full of neon. That may surprise or impress nobody, but that is the point: We all still have the ability. It is just that it has withered to a few short-term weather forecasts or similar. However, there is nothing stopping us from rekindling the deeper skills we once had. As we will see, few areas demonstrate the gulf between what we could once do and our ability today than our understanding of animal behavior in the wild.

Watch a bird flying toward a tree and you will be able to tell whether it is about to land on that tree or fly past it. This is not because you can read the bird’s mind, but because you can read its body language. If you don’t believe you can do this, try it. Watch a bird in flight and pick the moment you think it’s about to land on something. It will be before its feet touch down. Now ask yourself, how did you know that the bird was about to land?

Birds fan their tails and change their angle of flying and their speed just before landing, which means that their bodies go from near horizontal to pointing slightly upward and this angle increases sharply just prior to landing. It is the way both birds and aircraft can go from flying quickly through the air to landing on something slowly and safely, without falling out of the sky.

Our brains are picking up these clues all the time and making sense of them as best they can. There are thousands of them around us, all of the time, and we interpret many without realizing it. Your brain can tell that the bird is about to land because it has enough information from your senses, but this is the interesting thing: If asked, you might struggle to describe exactly how you knew it. Your brain made sense of the bird’s body language without bothering your conscious mind with the details, a classic difference between fast and slow thinking: The fast part knows things that the slow part can’t articulate. Thanks to photography and careful studies, we now know that ducks have four distinct stages of landing, including a certain head angle and bringing their feet forward. But we knew this already; we know what a landing duck looks like, we just didn’t have scientific labels for each of the stages.

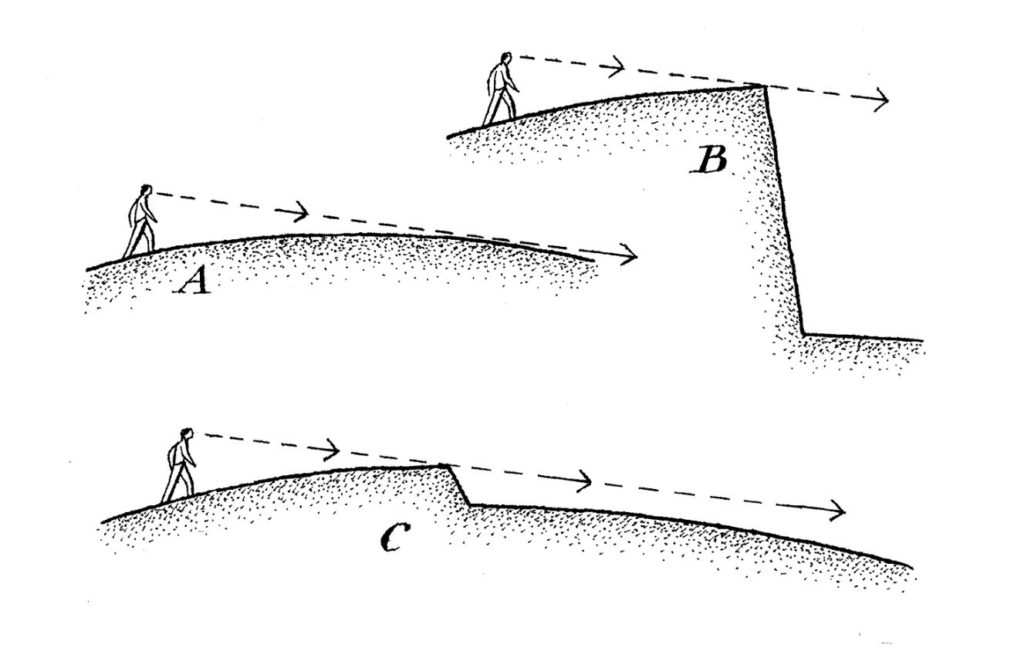

Imagine you’re walking in an area that you don’t know well and you’re being watched by a friend at the top of a steep hill. Your friend watches you walk quickly and confidently over the crest of a gentle hill, then slow down as you approach the crest of a dangerous precipice. Afterward they ask how you knew to slow down before the big drop.

“Well, I could see that there was a steep drop coming up,” you answer.

“Yes, but how? Could you see what was on the other side of each crest?” she persists.

“Um, no. But one felt dangerous and the other didn’t. I don’t know why.”

But, of course, you do know. Your brain has grown accustomed to noticing the subtle differences in the way the landscape changes as you approach a gentle hill compared to a sharper drop, even if you don’t appreciate exactly what it’s doing. The brain’s not perfect at this. I’m sure you’ve had those experiences where you find yourself gingerly treading toward an edge, only to find that it is a small dip followed by a kind slope that rolls away. Your brain has picked up the steep edge and prompted you to take a safety-first approach in that situation. All it senses is that there is a sharp drop; it doesn’t have the information to tell you that it’s only a tiny one.

All of this so far is straightforward stuff, by which I mean that these are skills we have retained, even if we spend little time outdoors compared to our ancestors. But I shall demonstrate how it is possible to develop such skills to a much higher level.

People who still spend long periods outdoors, particularly if they are focusing on certain areas, talk of this greater ability. The language may vary, but the experience is similar and points to an ancient sense of extraordinary awareness. Rob Thurlow is the ranger in my local woods, and we often discuss our experiences there. He has spent thousands of hours monitoring deer behavior.

“Sometimes you just feel the eyes on you,” Rob told me, referring to the fairly regular experience of knowing that a deer has clocked him, even though he’s looking the other way. I know exactly what he means and have had the same experience, as have many others. Joel Hardin, who was a professional man-tracker with US law enforcement for many years, sometimes had a strong sense that he was very close to a fugitive: “I just had a feeling.” And he was usually right.

When it is unclear how these sensations come about, they can be given labels, like “psychic” or “gut feeling” or “sixth sense,” but whenever we use such words or phrases, we are alluding to the fact that the evidence has been sorted out using our fast thinking. There is no right or wrong with the labels we choose to use for this—it is hard to be precise in language about something that goes on inside our heads that we can’t feel happening—but I shall describe it as “fast thinking” or “intuition,” one being the active process, the other the general ability.

From suggesting that our distant ancestors would be able to do The Times crossword if they were given the cultural framework, it follows that we can regain our ability to sense the outdoors as they did. That may sound daunting, but it is the framework that is important. Besides, you are already using these skills every day in your work and at home. All we are talking about is moving us back along the scale outdoors. Let’s look at a few examples that demonstrate that we can still do this.

If someone asks you whether it is night or day, it is not a taxing question to answer. If an insect lands on the back of your neck, you will swat it away without hesitation or contemplation. If you see the trees swaying outside a window, you instantly sense that it’s windy. Through the same window on another day, you see the heat haze rise off bright pavement and your brain tells you it’s hot without your asking it. Walking along a track down a hill, you see two small, bright elliptical objects on the ground in the distance that are colored like the sky. Before reading on, work out: What are these bright objects? That last question was a bit sneaky. Here, I have tried to lay a friendly ambush by asking your slow thinking to do something your fast thinking is better at. The answer is that you are looking at water, a pair of puddles on the track ahead of you. You may have worked that out by considering the evidence presented, the biggest clue being that these objects were the color of the sky—when viewed from a shallow angle, water acts like a mirror. But whether you got the answer to this before reading it or not is unimportant. The key point is that if you were actually doing the walk, you wouldn’t have needed to consider the evidence or think slowly about it; your brain would have recognized the shape, color, and situation of the objects, automatically compared them to those with which it was familiar in that setting, and presented the answer to you. And this would have happened whether you wanted it to or not. In reality, you couldn’t not have recognized the puddles.

Let’s consider situations where we use both types of thinking. The other night I took my two sons out on a night walk. As we were returning home we saw the clouds suddenly brighten.

“Whoa . . . what was that? Was it lightning?” Vincent, my ten-year-old, said.

“Yup,” I replied.

To me, it was obviously lightning, but my younger son hadn’t yet built enough experience of it during night walks to recognize it instantly. He had to think about it. His cogs were probably sifting through a process like This: sudden very bright light in a cloudy sky . . . search memory for known images that fit . . . only one so far . . . lightning?

All three of us recognized the lightning, albeit in slightly different ways.

There was another strike.

“That was a big one! Is it close, Daddy?” Vinnie asked, a little anxiety in his voice.

“No, not close, but let’s see how far. One elephant, two elephants, three elephants . . . fifteen elephants . . . twenty-five elephants . . . It’s still a long way off, more than five miles away.”

“How do you do that again, Dad?” Ben asked.

“We count the seconds, by counting elephants, until we hear thunder, then divide that number by five to get miles, or divide by three to get kilometers.”

Because there was little wind, it wasn’t raining, and the thunder had not arrived immediately after the lightning, I had known straight away that it was not a storm we needed to worry about yet; that was intuitive. By the time the elephants arrived in our conversation, we were all using slow thinking to build a more detailed picture of where it was.

When Vincent first asked me whether the flash was lightning, his fast thinking had sensed something that surprised and alarmed him. When that happens to any of us, our fast system bumps it over to our slow system to analyze. If you’re walking down a street at night and sense that the person coming toward you is not behaving normally, you will begin to analyze the person and situation more deliberately. Fast (sense) to slow (analysis).

If you are at a party and hear your name mentioned in a conversation on the other side of the room, your attention switches to that conversation. You may then hear the rest, including references to your charm and good looks—let’s give human nature the benefit of the doubt here. But if you then tried to remember what those people were talking about before they mentioned your name, you wouldn’t be able to because you weren’t listening carefully enough. The volume of the conversation hadn’t changed, but by focusing your conscious slow thinking on it, you could make out what was being said from that moment onward.

Here’s the weird thing: How did you hear your name being mentioned in the first place, since you weren’t listening carefully at that point? That was your fast unconscious thinking constantly scanning your environment for threats, and nothing is more threatening to the modern tribesperson than gossip.

If all we could do was divide up the types of outdoor thinking into fast and slow, it would remain an academic exercise and do little to improve our experience or ability in nature. The next step is noticing how and where our brains engage fast thinking instead of slow. This is something to which I have given a lot of thought over the past few years. Incidentally, this thinking has been mostly “slow,” sometimes painfully so. But there has been the occasional fast moment. We all experience sudden fast moments in our work and play. They are rare but delightful, and we call them “insights,” or “aha!” moments.

“Yes! Brilliant! That’s how we can solve the problem and meet the impossible deadline!” Or, “Of course! That’s why Helen didn’t react as I thought she would. She’s in love!”

Gary Player, a very successful golfer, was practicing difficult shots out of a bunker. He managed to sink the ball in the hole twice in a row. A Texan who was watching and couldn’t believe his eyes offered him a hundred dollars if he could do it a third time. In the ball went. The Texan handed over the cash, adding that he thought Player was the luckiest person he’d ever seen.

“Well, the harder I practice, the luckier I get,” Player replied.

I’m sure he wasn’t the first person to use that line and he won’t be the last, because we all know that time spent doing things repeatedly hones our skills. That expression, “hones our skills,” is another way of saying that our fast thinking becomes more adept through practice. Outdoor skills are no different from sports skills or any others; they take practice.

Also by Tristan Gooley:

Excerpt from The Nature Instinct: Relearning Our Lost Intuition for the Inner Workings of the Natural World. Copyright © 2018 by Tristan Gooley. Illustrations copyright © 2018 by Neil Gower.