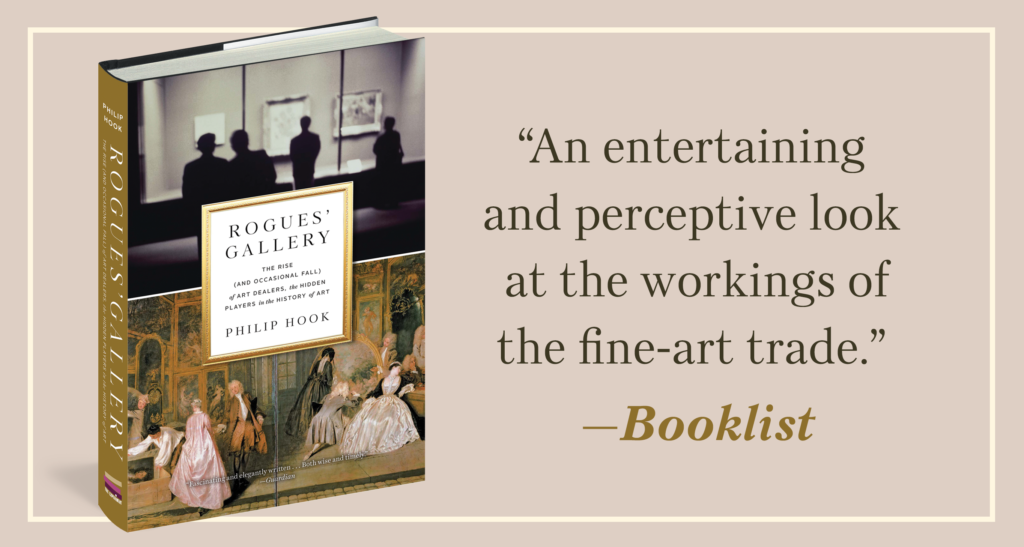

In Rogues’ Gallery: The Rise (and Occasional Fall) of Art Dealers, the Hidden Players in the History of Art author Philip Hook, Sotheby’s board member and senior director of Impressionist & Modern art in London, explores the hidden universe behind how the world’s most spectacular works of art are sold. Art dealers act as the puppeteers of the art industry—hidden from the public view, but masterfully maneuvering all the strings. Utilizing his forty years of experience in the art market, Philip Hook crafts a remarkable narrative journey through the history of art dealings—introducing readers to a slew of characters as colorful as the masterpieces they sell.

In anticipation of this forthcoming release, we spoke to Philip Hook about the past, present, and future of art dealing.

Q: Your book is titled Rogues’ Gallery—can you explain the title? Is the art world full of rogues?

Philip Hook: No, not all art dealers in history have been rogues. Some have been outstanding scholars and connoisseurs, and some have been heroic pioneers of modern art. But there is an endearing seam of roguery—or you could call it romanticism—running through the history of art dealing. What you have got to understand about art dealers is that they are selling a unique commodity. Art is not something functional. It’s a commodity with a value of disconcerting elasticity,

because what’s really being sold is a heady mixture of intellectual and aesthetic stimulation, spiritual benefit, social and cultural status, and investment opportunity. Given that heady mixture, it’s not surprising that dealers are sometimes guilty of a certain romanticism when it comes to pricing.

Q: In your introduction, you include a quote from Marcel Duchamp regarding his opinion of art dealers: “Lice on the backs of the artists.” Can you explain the root of this sentiment and whether it is still a popular opinion among artists?

PH: Artists look at the commission that dealers take on selling their work and are sometimes resentful. But the best dealers offer a promotional service that in the long run benefits artists (and their prices). And some dealers are great nurturers of artistic talent. I love the description that the American artist Robert Longo gave of his dealers Janelle Reiring and Helene Winer: “I’m the car crash and they’re the ambulance.”

Q: You go on to explain that, despite artist opinion, the art world would be vastly different today without art dealers—why is that? What crucial role have they played?

PH: The importance of the role of art dealers in the history of art has not fully been recognized. They are important in two ways. They help to form taste in the art of the past—look at Joseph Duveen and the influence he had on what the great American collectors of the early twentieth century bought, which in turn became the nucleus of the great American museums. And secondly there are those dealers who handle the work of living artists and in so doing play a very significant part in the development of modern art. If you look at the pioneer dealers in Paris either side of 1900, men like Paul Durand-Ruel, Ambroise Vollard, and Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler, it’s clear that they had considerable influence on what the Impressionists, the Fauves, and the Cubists painted.

Q: Your book is a history of art and its dealers—what are some ways art dealing and the “business” of art have changed from the seventeenth century to today?

PH: It’s a fascinating development. In the seventeenth century art dealers are often artists themselves, selling their own and other artists’ work. By the nineteenth century, the age of the entrepreneur, art dealers become distinct from artists. The great dynastic dealers like the Duveens and the Wildensteins start business and are hugely successful catering to the demands of the new wealth. But one thing is constant from the seventeenth century onwards: The most successful dealers are the ones most prepared to travel, to source art in one country and sell it in another.

Q: The history of art dealers is inextricably bound to the history of great artists, and your book is full of Matisse, Van Gogh, Cezanne, and more. Of course, every artist and his respective art dealer have a different dynamic, but can you explain how one position generally influenced the work of the other? Was the work of the greats influenced by art dealers?

PH: Picasso’s relationship with his dealers in the years 1910–1925 is an interesting example. Up till 1914 he was a Cubist, and he was supported and promoted by his dealer Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler in an almost Messianic way. Kahnweiler really believed in Cubism and relished the challenge of selling what was very difficult contemporary art that not many people understood. After the First World War Picasso changed dealers. His new man was Paul Rosenberg, a more worldly figure who launched Picasso into fashionable circles. This meant that Picasso became a figurative artist again, and much more accessible. As a result, Rosenberg managed to increase Picasso’s prices four-fold in the 1920s. Picasso liked that. In this sense Kahnweiler and Rosenberg are an interesting contrast. The relationship between the artist and the collector is mediated by the dealer. The dealer is like a two-way radio. On the one hand, he’s selling an artist’s work to a collector by interpreting and explaining that artist’s work to the collector. But he’s also interpreting the buyer to the artist. This is what buyers want; he’s telling the artist, adapt your work to meet their taste. Kahnweiler was primarily an interpreter of Picasso to the public. And Rosenberg was primarily an interpreter of the public to Picasso.

Q: A chapter is devoted to US art dealing—historically, how did it differ from its European counterparts?

PH: In the nineteenth century, the most successful art dealers in America were Europeans who came over to sell European art to an expanding—and aspirational—American market. There was also a big influx of major European art dealers to America in the 1930s and early 1940s as they fled Nazi Germany. But the big change comes once American artists start leading the world after the Second World War with movements like Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. This in turn creates a new generation of great American art dealers.

Q: The final chapter reflects on art dealing today—do you think it is “better” for its rich history, or do you think the profession has suffered? What do you imagine is the future of art dealers?

PH: As long as there are collectors there will be the need of art dealers to find them works of art and to advise them on acquisitions. But, as auction prices spiral, the traditional template of the art dealer buying for his own stock and then reselling at a profit has become unsustainable. With the exception of a few major global businesses, art dealers today must reinvent themselves as curators, advisers, and brokers.

Q: You also worked for many years as an art dealer—how did you find the profession?

PH: Art dealers are a marvelous mixture of actors in the human comedy. They comprise scholars, eccentrics, dangerous charmers, and brilliant salesmen. My favorite memory of an art dealer is of the late Billy Keating, a successful London dealer in Impressionism, who later in life became a devout Roman Catholic. One day he went into the Church of the Holy Redeemer in Chelsea to pray for the recovery of the art market. When he came out he found that his Porsche had been stolen. It somehow sums up the triumphs and disappointments of being an art dealer.

###

This interview can be reprinted in part or in its entirety with the following credit line:

Interview with Philip Hook, author of Rogues’ Gallery: The Rise (and Occasional Fall) of Art Dealers, the Hidden Players in the History of Art (The Experiment, October 2017). theexperimentpublishing.com

Rogues’ Gallery is available wherever books are sold.