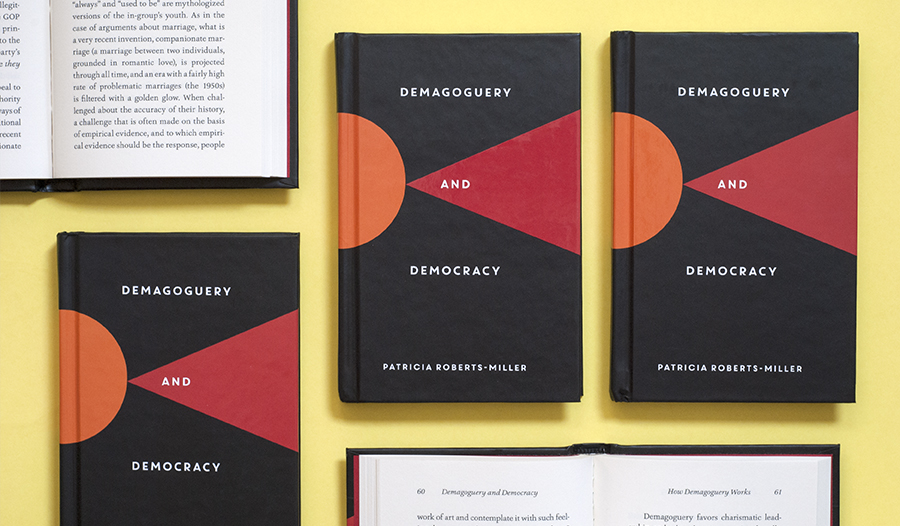

This guest blog comes from Patricia Roberts-Miller, author of Demagoguery and Democracy.

Patricia Roberts-Miller, PhD, is a Professor of Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Fanatical Schemes: Proslavery Rhetoric and the Tragedy of Consensus, Voices in the Wilderness: Public Discourse and the Paradox of Puritan Rhetoric, and Deliberate Conflict: Argument, Political Theory, and Composition Classes.

The Easy Demagoguery of Everyday Politics

Recently, where I work, a young man with mental health issues stabbed several people (including a person of color). He was quickly subdued by campus police.

In July of 1835, some gamblers were lynched in Vicksburg, Mississippi, after a typical pre-lynching “trial.” An early account says it was because they behaved badly at a fourth of July celebration.

Both incidents were quickly transformed into signs of a deliberate plot to exterminate whites. And, despite efforts to debunk those renarrations, those alarmist versions remained. Those second narratives, and how they became impervious to disproof, signify larger problems with the normal political discourse of the antebellum era and our own. I could have picked another pair—the 1835 American Anti-Slavery Society pamphlet mass mailing and Benghazi, fear-mongering about slave insurrections and claims of voter fraud—and the troubling similarity would remain. The similarity isn’t about the incidents, but about how they were transformed into alarmist narratives that resist all attempts at refutation. It’s about the easy demagoguery of everyday politics.

In the case of the tragedy at my university, it was almost immediately reported on various social media that the assailant was targeting white “Greek” males as part of a Mayday uprising, and that it was simply one of many simultaneous stabbings (it wasn’t any of those things). And, although that version has been repeatedly rebutted, it remains like a doppelganger of what actually happened, lumbering around the internet.

The 1835 lynching of gamblers similarly morphed into a fantastical narrative of vigilant supporters of slavery having unearthed and barely prevented a massive conspiracy on the part of John Murrell (a con artist who was at that point in jail) to instigate an uprising of slaves that would result in race war, with the goal of the killing of all whites. This incident wasn’t the only one that purported to prove that abolitionists advocated race war, and that slaveholders were potential victims of extermination (such as the Charleston mass mailing and various insurrections that didn’t happen), but it was cited in the next Congressional session as proof of abolitionists’ motives, and used to support the infamous gag rule (which prohibited the reading of anti-slavery petitions in Congress, an extraordinary act).

It’s understandable that initial rumors were false—immediate reports almost always are—but those false narratives continue to circulate in various informational eddies, with the consequence that the (non) event was used to support claims of a (non-existent) trend. In both cases, initial reports were accurate, and were, in many places, replaced by the later versions. In the places where the later version prevailed, nothing seemed capable of dislodging the misinformation. Since both narratives of the specific incident were used to confirm the perception among some people that there was a trend of deliberate extermination, the consequence was that there people genuinely frightened for their lives over something that never happened.

Humans love stories, and we tend to find claims more persuasive when they seem to fit within a familiar narrative. Informational pockets can end up creating a circle of belief: The grand narrative is proof that the mini-narratives are true, and mini-narratives are proof that the grand narrative is true. How, then, is someone within one of those pockets supposed to come to understand that they are misinformed?

Those grand narratives have tremendous impact on policy decisions. People are more willing to support punitive policies against a group they consider dangerous. If they live in an informational world in which they are told, over and over, that their very existence is threatened by that group, they will be willing to support punitive, even unjust, policies.

And that is how authoritarianism arises. People who think of themselves as kind and compassionate come to be persuaded that we are in what the philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls “a state of exception.” Normally, we would support the rights of all individuals, we tell ourselves, but this group is so dangerous (as is made clear by those various incidents) that we will create an exception for them. In general, we condemn authoritarian policies, but our situation is so dire that we “have no choice,” we tell ourselves.

What happened at my campus is heart-breaking. And it has nothing to do with a larger narrative about race. But there are people who live in informational enclaves in which it proves that they are threatened with extinction, and they are therefore justified in acts of violence.

The doppelganger lumbers on.