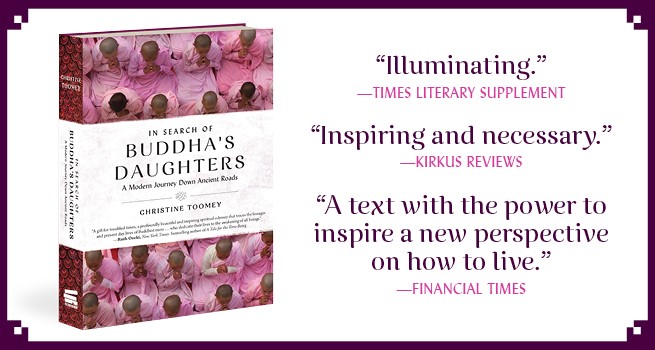

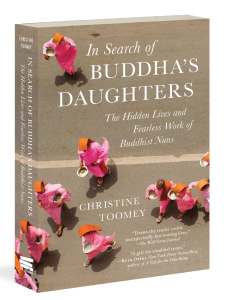

In Search of Buddha’s Daughters: The Hidden Lives and Fearless Work of Buddhist Nuns chronicles the 60,000 mile journey—both spiritual and physical—undertaken by award-winning journalist Christine Toomey to meet and learn from some of the world’s most incredible and inspiring Buddhist nuns.

Who are these women? What motivates them, and what stands in their way? From Nepal to California, Christine Toomey shares the stories of these unforgettable women who reveal the blessings—and perils—of carrying a 2,500-year tradition into the twenty-first century. Often denied equal status with monks, they are nonetheless devoted—to their faith, and to change.

Who are these women? What motivates them, and what stands in their way? From Nepal to California, Christine Toomey shares the stories of these unforgettable women who reveal the blessings—and perils—of carrying a 2,500-year tradition into the twenty-first century. Often denied equal status with monks, they are nonetheless devoted—to their faith, and to change.

Now available in paperback, this is perfect book to celebrate the diversity of women’s experience for Women’s History Month.

To celebrate the release of the new paperback and Women’s History Month, here is an interview with author Christine Toomey about the remarkable journey that she undertook.

Question: In Search of Buddha’s Daughters is the culmination of a massive undertaking—you traveled over 60,000 miles in two years, retracing the footsteps of Buddhism’s spread across the world and interviewing a host of incredible and empowering women along the way. What inspired you to start this journey, and at what point did you decide to dedicate so much time and energy to this project?

Christine Toomey: As a foreign correspondent and feature writer for The Sunday Times for more than twenty years, much of my journalism focused on human rights issues in places like Bosnia, Kosovo, Gaza, Iran, Colombia and elsewhere in Latin America. So it was through meeting Tibetan Buddhist nuns, who had been imprisoned and tortured in Chinese jails before fleeing across the Himalayas into exile, that initially inspired me to want to write about the lives of these women.

I first encountered these Tibetan Buddhist nuns in 2011 in Dharamshala, northern India, where I was on a journalistic assignment to mark the Dalai Lama’s historic transfer of temporal power to an elected prime minister. But it was the stories of these women that haunted me long after we parted, and I vowed to return one day to write about their experiences. When I started to research more about Buddhist nuns in other parts of the world, both in the East and the West, I discovered this extraordinary world of female strength and wisdom, and the idea of this book expanded: I felt instinctively that these were women who had a great deal to say to us all.

Initially, I had no ideathat the book I was embarking on would eventually lead me to travel 60,000 miles around the world listening to their remarkable stories— a journey that took me through the Himalayas of Nepal and India, through Burma, Japan, and onwards in the West through California, Washington State, New Mexico and also Europe. But I quickly realised that the women I was encountering were amongst the most extraordinary I was ever likely to meet, and that their stories, as diverse and different as they are from the experiences of most women today, were both utterly unique and enthralling. It was then that I decided to step back from the journalist track I had been on for so long, in order to commit myself wholeheartedly to conveying as much as I possibly could learn about and from these women during a period of two years.

Q: You traveled to an extremely diverse series of locations, ranging from remote Himalayan villages to downtown San Francisco. In your book, you describe the different lives and experiences of the women you encounter in these places—what unifies them?

CT: The most fundamentally unifying characteristics of these women, I would say, are wisdom and compassion. Many of those I met are also very courageous, because it takes courage to follow the path that they have chosen. It’s definitely not an easy life. Many have had to overcome severe hardship and numerous hurdles in order to be able to follow the Buddhist monastic path. In some Buddhist schools nuns have traditionally been thought of as occupying a lower status than monks. There has been resistance, for instance, to them accessing higher levels of Buddhist teachings and to them advancing from the stage of a novice to full ordination. One Burmese nun I write about was sentenced to five years in prison after being effectively accused of “impersonating a monk” because she dared to become fully ordained.

Much of this is beginning to change now, and I write about the huge strides many nuns are making towards equality. My book opens, for instance, in a nunnery outside Kathmandu, where young nuns practice kung fu daily for both physical and spiritual empowerment.

But while some might imagine that the life of a Buddhist nun is one of quiet contemplation, untroubled by everyday concerns, this could not be further than the truth. Many of those I met are deeply engaged with the communities in which they live, and grapple on a daily basis with some of the most profound problems that many of us are likely to ever face. Some work in prisons, for instance, others work with the dying or are engaged in various forms of humanitarian work, and others travel the world teaching. Without the usual means of distraction and entertainment that many of us take for granted, there’s no doubt that these are women utterly dedicated to their chosen vocation. But there’s also a real gentleness and humour in many of the women I spoke with, as well as a typical down-to-earth female approach to life.

Q: Many of the women featured in this book detail personal experiences that have shaped their lives and beliefs. What was the process of talking with these women like? Were they hesitant to share or eager to tell their stories?

CT: Some of those I spoke with were hesitant about sharing their stories or talking about themselves at any length. At first I found this difficult to understand, but, slowly, I came to realize that part of the reason for this was that, from a Buddhist perspective, the constant self-dramas in which most of us wrap our lives are considered so ephemeral as to have little inherent meaning. The nuns were very patient and bore my endless questioning with good grace so that, gradually, their stories, some of them quite extraordinary, emerged.

Sometimes, I also had the impression that some of the women I interviewed, particularly those in the East, struggled to understand the point of some of my questions. Perhaps this was because my questions were inevitably informed by a western perspective on life, which relies heavily on logic, critical analysis, and certain cultural assumptions about individuality and society.

Throughout the time I spent writing this book, I listened to many people’s preconceptions of what sort of women might be drawn to become a nun, Buddhist or otherwise. But I found that the dynamism and determination of the women I met defied many of these assumptions. Though there are those who come to the monastic path following devastating loss or as a means of escaping adversity, I slowly started to see beyond this kind of biographical shorthand. I came to see that the internal shift and deeper sense of need that most of those I talked to feel is both hard for them to articulate, and difficult for another person to understand. I realised it required a deeper kind of listening.

On a purely practical level, the process of meeting and talking with some of the women in my book posed logistical difficulties. In addition to needing the help of interpreters in places like Nepal, India, Burma and Japan, I had to accept that some of those I wanted to meet could not be reached easily by email. In some cases I had to resort to writing letters and waiting quite a while for a reply. In others, I had to wait for those I wanted to interview to emerge from lengthy periods of retreat.

Q: Many of these women have gone to great lengths to practice as Buddhist nuns. Some have even risked their lives and freedom. What was it like meeting such determined woman, and what do you think drives their resolve?

CT: I felt it was a rare privilege to be able to spend time in the company of the women I interviewed for this book. We hear far less about those who come at life from a place of wisdom and bravery rather than hate and self-interest. But I really feel that there’s great strength to be found amongst these women because what drives them is a determination to cultivate a sense of peace, both within themselves and for those whose lives they touch.

These are all women who feel a calling to a larger purpose in life, and in this rapidly changing age that forces many of us to question what is meaningful, the path these women have chosen is not only different, but somehow defiant. Our modern world often disdains the inner life, disparaging it as “navel gazing.” But the journey through life these women have chosen is a journey inwards, rather than outwards in search of material success, security or personal triumph. It’s a journey through a spiritual landscape fraught with hardship but offering great reward.

When I witness the uncertainties of my daughter’s generation and remember those of my own, about role models, career building and what being a successful and happy woman means in a society obsessed with body image and material possessions, exploring the lives of women who are drawn to asking different questions about life, and finding different answers, offers a very refreshing alternative perspective.

Q: As discussed in your book, Buddhist-inspired ideas such as mindfulness continue to gain popularity in the West, even among secular audiences. Do you think that this is just a trend, or does it represent a more fundamental shift in the way Westerners are starting to reflect on their lives?

CT: You could say it’s a trend in the way that mindfulness has taken off and become almost a buzzword in the media. But I believe the reason it has taken off and will continue to gain popularity is because it’s been found to be so effective in so many different settings, not just in the West, but globally. There are now programs in many countries around the world applying the practice of mindfulness in schools and universities, for instance in the military, amongst politicians, performers, those coping with chronic pain and parents wanting to better cope with the challenges of raising children. Inevitably, there are a growing number of mindfulness smartphone apps.

The way that a growing number of businesses have hitched their fortunes to what some see as a mindfulness bandwagon, with promises of increased productivity and reduced stress, has invariably led to concerns about what some dub “McMindfulness,” and raised questions about under-qualified teachers presenting themselves as experts on the subject. This is one of the reasons I trace the origins of mindfulness back to its monastic origins and explore the lives of women who dedicate themselves to this practice in a very profound way, moving beyond the greater awareness and understanding it brings in order to match it with compassion and take it out into the world.

While many mindfulness programs are now taught on a purely secular basis, I think those that link the practice with its Buddhist origins do help to fulfil a spiritual need that many now feel in the West. Especially in this age of information overload, it provides a tool to help those who practice it stand back and reflect on life.

There’s also no doubt that the growing popularity of mindfulness is largely due to the genius of people like Jon Kabat-Zinn, who was able to prove the medical benefits of mindfulness in helping people cope with stress and pain. I think a large part of the appeal of the practice, and the reason it is likely to continue to spread, is due to the fact that it has now been scientifically proven to work.

Q: When you started this journey, what were you looking for? Were you able to find it?

CT: When I first started writing this book, I thought of it as an essentially journalistic undertaking. I felt very strongly that writing about the experiences of Buddhist nuns in different parts of the world would add a valuable voice to the different experiences and challenges faced by women today. In many ways I saw the Buddhist nuns’ journey as a metaphor for the struggles and triumphs of women the world over and throughout time; the alternative way of life they have chosen, a testimony to the way women survive and adapt.

But writing the book quickly took on a far more personal sense of urgency because, in the year I spent planning and setting up interviews before taking to the road, both of my parents died within a few months of each other. My mother, who was a writer, and a large part of why I became a journalist and a writer, passed away quite suddenly just before I set off traveling. This was a huge shock. So by the time I started my journey I was in a different space and found myself asking questions in a different way. As a result, the book that emerged is a far more intimate exploration of the wisdom of the women I met.

Through the hundreds of hours I spent talking with Buddhist nuns all over the world, I found myself not only wanting to share their extraordinary stories, but also in need of time and space to stand back, reflect, and heal. I found great comfort in following some of their practices and hearing the hard-won lessons they have learnt on their own paths to enlightenment.

Q: Although this book is not autobiographical, you are also writing about a personal journey. What were you able to learn about yourself on this trip, and how has it changed your perspective on life?

Q: Although this book is not autobiographical, you are also writing about a personal journey. What were you able to learn about yourself on this trip, and how has it changed your perspective on life?

CT: One experience that made a particularly deep impression on me was the time I spent in a Zen training temple in Japan, where, together with Zen Buddhist nuns, I followed a strict regime of meditation called a sesshin. Each day began at 4am, and the practice was to sit crossed legged, facing a bamboo screen, simply observing thoughts and physical sensations without either repressing them or getting carried by them. Just letting them pass. It meant sitting still for long periods and not moving when bones and muscles ached. Despite years of yoga practice and a fairly supple body, in the beginning it was agony.

But paying close attention to what was really going on inside my head during this time was illuminating. With no means of escape or distraction I began to see clearly how even the most distressing thoughts and feelings passed more easily if I simply allowed them to be. I saw how this practice of being aware, rather than constantly reacting to the thinking process of staying mentally present, without thoughts playing out patterns determined by remembered pasts or projected futures, allowed a more peaceful state of mind.

It was a wake-up call to realize how much of our time is spent literally “lost” in thought, blown back and forth by troubling emotions. It was a lesson in being truly present and its effects have stayed with me.

Q: You have been covering foreign affairs at The Sunday Times for quite a while now. Why did you decide to take this journey at the time that you did, and why do you think that it is an especially important time to write this book?

CT: We live in a world numbed by the amount of attention paid to violence and terrorism, and political and religious power struggles. There’s no doubt we need to shine a light into those dark corners of the world, where atrocities of one kind or another are committed. I have many brave journalist colleagues who put their life on the line to do this every day.

But I believe there is a hunger for more signs of hope, a thirst for more attention paid, not to those determined to drive us ever further into the abyss, but to those who master the far more difficult task of fostering peace. The women I write about in my book are masters of this. Their lives are dedicated to cultivating wisdom, peace, and enlightenment.

After so many years spent writing about conflict, I realized that much of it focussed on violence directed towards women and children, and a kind of sadness had settled in my bones. Encountering such female wisdom restored my faith in the ability of the human spirit to flourish, despite sometimes appalling hardship. As one senior Vietnamese nun, exiled from her home country since the Vietnam War, told me, “You have to stop the war inside yourself.” Her words made a deep impression and I meditate daily with this in mind together with many of the other lessons I learnt through the journey of writing this book. This has helped to restore my spirit and energy.

Q: What do you hope readers will be able to learn and takeaway, either about themselves or about the broader world, by reading this book?

CT: On one level I hope readers will enjoy being taken on a journey to discover different countries and ways of life that are both unfamiliar and fascinating. This book opens a door to a rarely glimpsed world of ritual, discipline and enlightenment in places where few visitors go; remote nunneries, hermitages, monasteries and temples as far away as Upper Burma, Japan, the Himalayas of Nepal and India, as well as closer to home in the US and in Europe, for instance in the Highlands of Scotland and the South of France.

On another level I hope readers may also be as inspired as I was by the stories of very different lives transformed. I see this book as an exploration of spirituality in modern times by thoroughly modern women of all ages and from a huge diversity of backgrounds. In the East, for instance, one of those I interviewed had been an anti-terrorist policewoman, another was a princess, and another a very successful novelist and one-time author of erotic fiction. In the West they included a former Washington political aide, a US naval officer, a journalist, a former banker and a one-time advertising executive, as well as former nurses, teachers, and performing artists.

It’s hard to summarize in a few words what I hope readers might learn from the wisdom of the women I interviewed, as I feel that I learnt so much from the time I spent with them. To give just one small example, though: when I asked some of them what lesson from monastic life they would most cherish and carry with them were they ever to return to lay life, more than one said it would be “to constantly let go.” I hope that perhaps, through reading this book and understanding what the women I write about went through in order to be able to continually put this into practice, it might make it easier for the rest of us to do the same.

This interview can be reprinted in part or in its entirety with the following credit line:

Interview with Christine Toomey, author of In Search of Buddha’s Daughters: The Hidden Lives and Fearless Work of Buddhist Nuns (The Experiment, March 2017). www.theexperimentpublishing.com