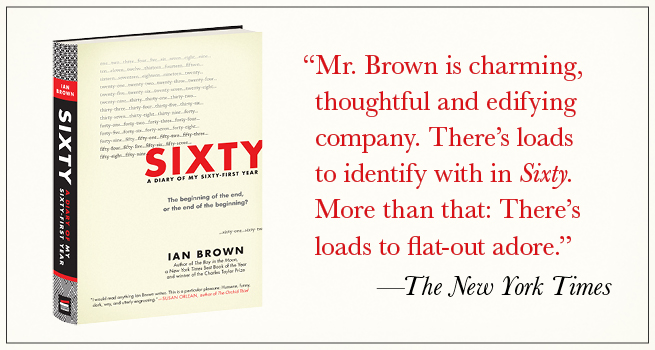

Sixty is the diary of author Ian Brown’s sixty-first year. An unflinchingly funny look at the thin line that separates the middle-aged from the elderly. The New York Times is hailing the book as having “loads to flat-out adore.”

To celebrate the book’s publication, Ian is coming to the U.S. for a book tour!

Ian Brown US Tour

Sunday, September 18 at 5:00pm

Politics & Prose

5015 Connecticut Avenue Northwest

Washington D.C., 20008

Tuesday, September 20 at 12:00pm

92nd Street Y

Lexington Avenue at 92nd St

New York, NY, 10128

Wednesday, September 21 at 7:00pm

Vroman’s Bookstore

695 E. Colorado Blvd.

Pasadena, CA, 91101

Thursday, September 22 at 7:30pm

Town Hall Seattle

1119 Eighth Avenue

Seattle, WA, 98101

In this Q&A Ian answers a few questions about what inspired him to keep a diary during his sixty-first year.

Question: Ian, what inspired you to write a book about turning 60?

Ian Brown: I began to notice changes in my body, which, like most people, I had relied on to make most of my decisions since the age of 15. Before that you are dependent on others. Then, at around 60, which is the National Institute of Health’s official age marking the onset of aging, your body becomes less reliable. For me it started with my hearing. I was at a story meeting, having just read a book about Cape Horn, when another writer said he wanted to write about gay porn. I, naturally, said, “Oh, I love Cape Horn.” The other writer looked at me and said, “I didn’t think you were the type.” And these small letdowns extended to my mind as well. Because I was slowly balding, I started to use hair gel. One morning, after rubbing some gel on my hands to rub through what is left of my hair, I applied it to my face, thinking it was sunscreen. Because of course, now that I am sixtyish, I have to wear SPF 10,000 sunblock as well. Sixty is the Age of the Unguents. In any event, these occurrences got me thinking about how we age, physically, and why it seems to come as a such a shock to most of us, psychologically and emotionally, when in fact we all age from the day we are born. But something makes us want to live in denial of that fact.

Q: Why did you want to write a book about aging when people say 60 is the new forty?

IB: Because anyone who is even approaching sixty who is honest knows that there are signs you cannot deny. I was waking up thinking either, what’s the point of going on if I’m going to die (the Phillip Larkin response), or, “Fuck death!” (the Harold Pinter response). I couldn’t figure out why. So I thought if I kept a diary of my aging for a year, and read about the physical aging process, and anything else I could get my hands on, I might notice some of the details of time passing, and be able to slow them down and figure out what was happening to me.

Q: Are many people in denial of their aging?

IB: You are kidding, right? Everyone denies it. We all deny the fact that we are aging from the moment we are born. Simone de Beauvoir said everyone lives a double life where aging is concerned: the outer person denies getting older, while inside them is a double who ages constantly. Eventually they can’t ignore the aging double inside them anymore, whereupon their double life blows apart, and they have a mid-life or late-life crisis. (That’ why Goethe said “Age comes as a surprise to everyone.”) Your brain stops expanding, and begins it’s slow decline, at the age of 28; the elastin in your skin starts to disintegrate at 30, which is why your nose seems to get larger (your nose droops while your head shrinks); your bones are already turning to ash at 40. And no one gets out of it alive. The only question is, what does one do with that knowledge?

Q: What is it about that age that made you question where your life was heading?

IB: Regrets. The popular wisdom is that one should not have any, but I have never encountered any real human beings for whom that was true. If you don’t have regrets, then you have never known failure, and if you haven’t known failure, then you are either an imbecile or living an unexamined life of denial. And you know what they say about the unexamined life: it’s not worth examining. But at the same time, my regrets—and while I have lived a fairly successful life, by some standards, I still feel I missed lots of opportunities, to write, to make money, to have a different life path—felt toxic, and painful,. So I was keen to understand them, to see if they were excusable, droppable. And this led me to realize that most of us approach aging—and this is partly our own doing, and partly the pressure of the youth-oriented culture we live in—as a form of failure. Which is ridiculous, but widespread.

Q: Now that you’ve passed your 61st year, what you are you most excited and/or concerned about for your next milestone: 70?

IB: Frankly, to my immense surprise, I look forward to each day more than I ever did before: I like to see if I can make it mean something, and if I can’t, I like to figure out why. It’s a useful little exercise. I would like to write a sequel at 70, but I am in no rush to get there, as they say. Because I also know, as Phillip Larkin, the great British poet (and the laureate of aging) pointed out, that each day brings me one step closer to the day when I will have no days left–whenever that day occurs. Not soon, I hope. But it will come, terrifying me all the way. And while, like Larkin, I have a hard time conceiving of a world without me in it, it is not beyond the ken of my imagination. Which, it turns out, is a good thing too—because it is the finite nature of our existence that makes the world seem so beautiful and exalted. But it’s very hard to understand that finitude before you turn 60. I know Keats did it at 24, but he was Keats.

Q: In your book, Sixty, you present a journal of your 61st year. How did you determine what should be included, and what should be left out?

IB: That’s an interesting question. I’m a journalist; I have been trained to notice what is supposed to be true and important, what other people tell me is true and important, what’s on the official, sanctioned agenda. (That’s why so much journalism is so boring.) But when you keep a diary, you are forced back on what you, yourself, actually find true, as opposed to what you are supposed to find true. Nicholson Baker, one of my favorite writers, once told me that when he woke up in the morning and found he had nothing to write about, he often jump-started his mental machine by writing about the best thing that had happened the day before. It was never what he expected it to be. And so a diary becomes an exercise in discovering what actually matters to you. It’s rarely predictable, the way the official journalistic agenda is. For instance, I spent a fair bit of time wandering the internet, trying to find out who else was 60: a disgraceful habit, but there you are. Oprah, is turned out, was 60, and so was Christie Brinkley. The latter is a supermodel, and the former is super rich, and I am neither. But they were both as close to the end as I was, and that, mark my craven words, was a huge and surprising comfort. And to my surprise, that is something readers respond to. So the short answer is, you think about including everything, but in the end, what actually matters to you stands out, because it secretly matters to others as well, and somehow, mysteriously, you can feel that.

Q: You are now 62. So, is life good in your seventh decade?

IB: I never thought I would say this, but yes. Increasingly, as I look back at my twenties, I remember them as an agonizing time: money problems, trying to find my voice as a writer, disastrous love affairs. My thirties were an improvement, but also difficult; in my forties I had kids, which was great, but also hard. The in my fifties I began to worry that I had missed the boat. It’s only now that I can be more radical, and define my life in less conventional terms.

Q: You are a highly-acclaimed journalist and writer. Did turning 60 spark you to set your sights on a significant career accomplishment?

IB: Yes. It made me resolve to write more, write more books, write a novel, write more fearlessly. Novelists like Martin Amis have made a career saying that if you haven’t made it by 40, you will never make it. I admire Martin a lot, but he is completely full of shite in that regard. His own best work came after 40, as does the best work of (I would say) a majority of artists, many of whom are or were still producing their most lasting work after 60: Picasso, Cassals, Hoagland, Hockney, Calvin Trillin, Matisse, Julian Barnes, Georgia O’Keefe, Scorcese, Tom Wolfe, Hayden. The list is endless.

Q: What advice would you have for someone half your age?

IB: Do everything you want to do that you are afraid to undertake for fear of failing at it. Because failure doesn’t exist, at least at that level. You simply try, study what happened, and move on.

Q: Who are some good models for turning 60 that we should look to as we approach this special age?

IB: See my last answer. But they don’t have to be artists. Jackrabbit Johannsen, the skier, was still skiing 100 mile trips at 90. The Duc de Richelieu got married at 85 or so, then impregnated his girlfriend and had a child at 90. He died in flagrant delicto at about 93. Marinoni, the famous bicycle maker, is in his 80s, and still peels off 100 kms a day. Hillary Clinton is in her 70s. This illusion that we’re all washed up at 50 and certainly by 60 is a creation of marketers, pure and simple—a way for capitalism to renew its customer base, and discard the one that has cottoned to its lies.

Q: You pose the question is sixty “the beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning?” Which do you personally see it as and why?

IB: Both. But especially the later. And thank God! Because turning 60 takes the frightening edge off existence, and lets you see it more clearly.

Q: The book starts with you looking at a photograph of yourself in your forties. Two decades later, what was the most unexpected advantage of aging that you’ve discovered?

IB: To my immense surprise, that many of the personal and intimate details I noted in my diaries are known and understood by other people. It’s the most personal details that seem to resonate most with others, if only we are brave enough to share them. Which in turn suggests that we are all, at our most intimate, the same. And if we are the same, then war are also equal. That’s a radical observation, and, to me, a comforting and exhilarating one. I think of it as the first gift of getting older.

###

This interview can be reprinted in part or in its entirety with the following credit line:

Interview with Ian Brown , author of Sixty: A Diary of My Sixty-First Year (The Experiment, August 2016). www.theexperimentpublishing.com