This guest blog comes from Tristan Gooley, author of The Natural Navigator and most recently, The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs.

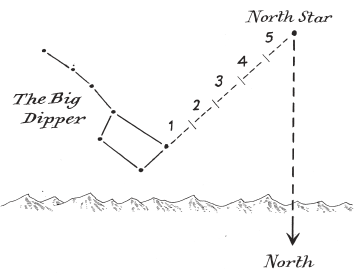

The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs is full of techniques for forecasting and tracking, and for walking in the country or city, along the coast, and by night. It’s is the ultimate resource on what the land, sun, moon, stars, plants, animals, and clouds can reveal—if you only know how to look! Here, Tristan talks about how we can all channel our inner Sherlock Holmes if we read the clues in the great puzzle that is the outdoors. The illustrations are by Neil Gower—straight from the book!

The Great Outdoors Mystery

by Tristan Gooley

From our love of Sherlock Holmes, through crosswords and jigsaws to Scooby-Doo and Sudoku, a pattern emerges. Humans like patterns, but we prefer puzzles and mysteries and if there is one thing we like even more than a puzzle it is spotting the clues that yield a solution. Animals solve puzzles out of necessity, humans do it for fun.

Our ancestors never had cryptic crosswords or the works of Agatha Christie to occupy their minds, but they had their own riddles to solve, all around them. These were puzzles born of necessity – where is the next meal coming from? How do I get home? Is that a storm approaching? Looking at modern humans these ancestors might well find themselves baffled by a more perplexing mystery. Why, for the past century, have we assumed that the deductive part of our brain must be put to sleep the moment we step outdoors?

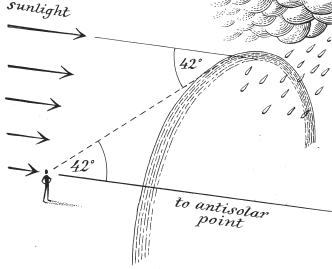

The natural world is teeming with clues, signs, puzzles and mysteries and they are far richer than any that will be found in the entire vast canon of whodunnits in fiction, film or TV. The pieces of these outdoor puzzles come clearly into view when we ask a few simple questions, like “Which way am I looking?”, and then scour our surroundings for the clues in nature that offer an answer. We can work out which way is north and forecast  the weather using the same rainbow—rainbows form exactly opposite the sun, which can make them dependable compasses. And since our weather comes from the west, rainbows in the afternoon suggest improving weather, but morning ones mean an imminent downpour is more likely. We can even judge the size of raindrops using the colors in a rainbow, once we know how to crack that code – every color reveals something about the raindrops, but the simplest clue is that a bright red band at the top means big raindrops – ‘lots of red means a wet head’.

the weather using the same rainbow—rainbows form exactly opposite the sun, which can make them dependable compasses. And since our weather comes from the west, rainbows in the afternoon suggest improving weather, but morning ones mean an imminent downpour is more likely. We can even judge the size of raindrops using the colors in a rainbow, once we know how to crack that code – every color reveals something about the raindrops, but the simplest clue is that a bright red band at the top means big raindrops – ‘lots of red means a wet head’.

There are hundreds of similar techniques that allow us to unravel the mysteries of the outdoors, methods that give the deductive part of our brains a chance to stretch and cut loose. But most of this knowledge has been allowed to wither and perish. Around the world, schoolchildren who hear the word ‘blackberry’ and wonder what one is might Google it, where they will discover that it is ‘a line of wireless handheld devices’. They will not enjoy a blackberry’s sweetness on the Internet and are unlikely to learn that this sweetness is a clue to direction. ‘Sweet is south’ is a useful mantra to remember, because the sugar in fruit is energy harvested from the sun, which is due south in the middle of the day – you get more sweet fruit and sweeter fruit in south-facing spots.

Food may actually offer the best clue for solving the mystery of why we have let so much of this knowledge go. For thousands of years one of society’s most pressing challenges was to produce enough food to fend off starvation. In the large parts of the West we largely solved this problem, but then as humanity so often does, we overshot and have now created an epidemic of obesity. This has forced us to reassess our relationship with food. An interest in quantity has evolved into a fascination with methods, provenance and quality. We now know that food is not all about calories or necessity, it can be a source of social and cultural richness. Cooking at home has not been the most efficient way to get calories into our bodies for a long time, fast food overtook it many decades ago. But we still cook at home and we often cook for a different reason to our ancestors – because it is satisfying and enriching beyond necessity. This can be the only explanation for the passionate renaissance in the most basic of food skills, like baking and even foraging.

We now find ourselves at a familiar stage on this timeline when it comes to outdoor skills like natural navigation. Our view of navigation has been shaped by a mantra of necessity for thousands of years – how do we get to where we want to go as quickly and efficiently as possible? We are close to solving that problem with the use of satellites and software, but once more we are in the process of overshooting the mark and this is robbing our journeys of the richness that our ancestors knew well. We can see the blandness creeping up on our travels in the maps we use. Maps have lost colors dependably over the past decades and our satnavs have now reduced a world of a million colors to three or four.

We now find ourselves at a familiar stage on this timeline when it comes to outdoor skills like natural navigation. Our view of navigation has been shaped by a mantra of necessity for thousands of years – how do we get to where we want to go as quickly and efficiently as possible? We are close to solving that problem with the use of satellites and software, but once more we are in the process of overshooting the mark and this is robbing our journeys of the richness that our ancestors knew well. We can see the blandness creeping up on our travels in the maps we use. Maps have lost colors dependably over the past decades and our satnavs have now reduced a world of a million colors to three or four.

Is natural navigation necessary to get from A to B in an age of satellite data on smartphones? No. Is the ability to find water using trees necessary when we can make it flow by waving a hand in front of a motion sensor? No. Is forecasting the weather with the help of bees necessary when there are supercomputers making forecasts for dedicated TV channels? No. Are these skills rewarding and satisfying well beyond that necessity? Absolutely.

It would be easy to argue that music, dance, theatre, poetry and dozens of other disciplines are unnecessary. But surely one of the broadest conclusions we can draw from our endeavors of the past century is that necessity is not a useful guide for finding fascination. Necessity is the enemy of mystery, but mystery is what lets our minds soar. It is time to turn every moment outdoors back into the puzzle it was always meant to be.

Tristan Gooley is a writer and navigator. His passion for the subject of natural navigation stems from his hands-on experience. He has led expeditions in five continents, climbed mountains in Europe, Africa and Asia, sailed small boats across oceans and piloted small aircraft to Africa and the Arctic. He is the only living person to have both flown solo and sailed singlehandedly across the Atlantic, and he is a Fellow of the Royal Institute of Navigation and the Royal Geographical Society. He and his school (UK) can be found online at naturalnavigator.com

Tristan Gooley is a writer and navigator. His passion for the subject of natural navigation stems from his hands-on experience. He has led expeditions in five continents, climbed mountains in Europe, Africa and Asia, sailed small boats across oceans and piloted small aircraft to Africa and the Arctic. He is the only living person to have both flown solo and sailed singlehandedly across the Atlantic, and he is a Fellow of the Royal Institute of Navigation and the Royal Geographical Society. He and his school (UK) can be found online at naturalnavigator.com