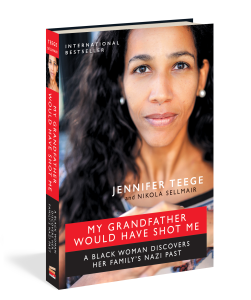

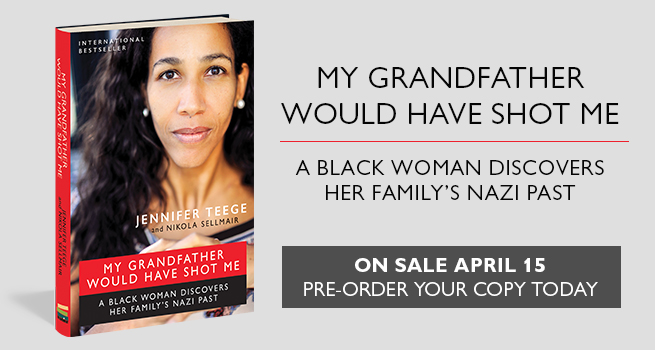

Publishing on April 15, Holocaust Remembrance Day, is an international bestseller, now available for the first time in English. This almost unbelievable story explores more than just the Holocaust, but also themes of race, adoption, trauma, depression, suicide, friendship, and more.

A Black Woman Discover’s Her Family’s Nazi Past

by Jennifer Teege and Nikola Sellmair

Q: Your true story reads like a perfect storm of unlikely circumstances. Your mother is German, and your father is Nigerian. You were adopted at age 7 by a white family, but still had intermittent contact with your birth mother and grandmother. You went to college in Israel, where you have many Jewish friends to this day, and you speak fluent Hebrew.

Then, at age 38, you picked up a library book by chance and made this stunning discovery: Your grandfather is Amon Goeth, the infamous Nazi commandant of Płaszów concentration camp. Even more, the woman you remember as your kindly grandmother lived with him in luxury at that very camp. And your birth mother, Monika—who kept these secrets from you—appeared in a documentary on the subject which premiered the very day after you found that book. Looking back, is there any one thing that was hardest for you to accept?

Jennifer Teege: There was no one point that was hardest to reconcile with. I have faced many challenges in life that I’ve had to overcome. It started with my birth: For any child, being given away by your parent is a traumatic experience that you carry with you for a lifetime. One’s self-worth is called into question. My mother was a single parent, and she placed me in a Catholic home for children when I was four weeks old.

In my case, another traumatic experience was added to the first. When I found out who my grandfather was from the book about my mother, my initial reaction was shock—first, shock that there was a book about my mother that I hadn’t been aware of, and next, shock that Amon Goeth was my grandfather. Like so many others, I had seen the movie Schindler’s List. I was terrified of that monstrous figure—and now I was petrified: Was it possible that I might resemble him? Today that fear is gone. I know that I am a different person.

Q: Following your discovery, you fell into a deep depression. Many descendants of Holocaust victims are haunted by their family’s past. Is it different for descendants of perpetrators?

JT: Victims’ and perpetrators’ families are both bound by silence, by the desire to forget. In Germany the Holocaust is taught in detail at school but seldom discussed within the family. Many people of my generation are afraid to ask exactly what their own grandparents did during the war, how they were involved. They are afraid of the truth. In victims’ families, the dynamic is somewhat different. Most don’t want to ask because they don’t want to traumatize the survivors further, or again. One might say that they respect the silence of the survivors.

Q: Did your discovery impact how you see yourself? Did it make you feel differently about your own children?

JT: Once I compared my life to a puzzle. There were so many pieces, but the frame was missing. I was unsure of where I fit in, and where my depression stemmed from. Today I can put the pieces into a frame, and they make up a clear picture—things aren’t in a big mess anymore. Of course there are still blindspots; everyone has them. The idea that I’m going to find all the pieces by the end of my life is unrealistic, but it’s also not important. Now I have a different way of assessing my feelings. Even if I have changed, I’ve remained the same person—I know who I am. I can live with the past now.

My children can, too. They are a whole other generation removed; for them it’s not their grandfather, it’s their great-grandfather. They are shielded, in part, by that greater distance.

Q: Even while grappling with depression, you extensively researched your grandfather and visited the sites of his crimes. Later on, you reconnected with your biological mother. What were you hoping to achieve?

JT: The questions started piling up in my head. I had to work through them bit by bit. First of all I had to confront my anger and disappointment toward my biological mother: Why did she reject me? It took a long time for my image of her to change. Today I see her not only as my birth mother, but also as a woman with her own story and history. She suffers from the weight of the past. She once said, “I live with the dead.”

I wanted to let go, to live in the here and now again, and be a good mother to my own children. On my path in that direction, Kraków was an important step. I realized that I am part of the third generation. I know now that I am not to blame, and the guilt no longer weighs heavily on my shoulders. That said, today I am occupied with the concept of responsibility. Everyone bears a responsibility to add value to their surroundings. I carry responsibility not only as a German woman, or as Amon Goeth’s granddaughter, but simply as a person.

Q: You waited a long time to tell your friends in Israel about your discovery. Why did you break off contact? When were you ready to approach them again?

JT: It was over two years before I could bring myself to reveal my Nazi connection to my Jewish friends. First, I wanted to come to grips with it myself, so as not to confront them with too many details.

Earlier, I addressed the sorrow in the families of Holocaust victims, the inability to cope with old fears and feelings. I didn’t know exactly what my friends’ stories were: Where were their relatives born? When were they killed, and how did they die? Was there a connection to Poland, to Płazów? So I was afraid of what my revelation would trigger for them. But my friends reacted in the most empathetic way imaginable—they cried with me.

Q: Amon Goeth—your grandfather—is the brutal Nazi commandant played by Ralph Fiennes in Schindler’s List. When did you first see the movie? How did it affect you?

JT: Many assume that I have watched Schindler’s List over and over. But I haven’t; I’m not sure why. I just don’t feel the need to. I did see it when it was first released—in the mid-nineties, while I was living in Israel. At the time, it was just a film to me; it didn’t have anything to do with me personally. I wasn’t suspicious when I heard the name Goeth, in part because the movie uses the Polish pronunciation, which is different than the German, with a shorter “th.” The movie touched me, but I was very conscious that it was a Hollywood feature, not a documentary.

Q: Many would say that your story is almost unbelievable, “stranger than fiction.” In your memoir you say “At age 38, I found the book. Why on earth did I pick it up off the shelf, one among hundreds of thousands of books? Is there such a thing as fate?” You also say, “I’ve realized that the book is meant for me, the key to my family history, to my life. The key I’ve been looking for all these years.” What do you make of the coincidences in your past?

JT: It depends on how you view life: forward-thinking or backward-thinking. When I first went to Israel in my mid-twenties, I didn’t go because I was German and wanted to make amends. No, I originally went for a vacation, fell in love, and stayed. I never dreamed that there was a close tie between the country and myself. Today, I know that the stay was fateful for me.

I like to use the tree as a metaphor. Everyone has their own genealogy, with roots, a trunk, and branches. We can develop and thrive in this system, but we can’t direct it. We all exist within a larger pattern that carries and sustains us.

Q: Your story is a bestseller in several languages. After 70 years, why do you think there remains such a strong interest in the Holocaust? And how does your story speak to readers, beyond history?

JT: The Holocaust was a genocide of gigantic proportions. That makes it so difficult to grasp. Why did so many people support the Nazi ideology, stay silent, look away, or participate? Why do people kick other people down? How do people turn into perpetrators? Our world is still struggling with the same themes: racism, extremism, and violence. My book doesn’t claim to have the answers; it seeks only to encourage contemplation. Along with the historical connections I’m interested in psychology—the toxic power of family secrets, depression and how to deal with it, and of course the search for one’s own identity. The book speaks to readers on all of these points in a single story.

Q: Why was it important that you share your story? What do you hope readers will take away?

JT: First of all, I didn’t write my story down with some specific, concrete goal in mind. But I thought that it was important to share my story in part because of a quote I read years ago, from Bettina Goering, another descendant of a perpetrator. She said that she and her brother had had themselves sterilized, so as not to produce any more Goerings. I think that that attitude sends the wrong message. There is no Nazi gene: We can decide for ourselves who and what we want to be.

Interview with Jennifer Teege, author of My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family’s Nazi Past (The Experiment, April 2015).

Pingback: An Unforgettable Summer Read | The Experiment