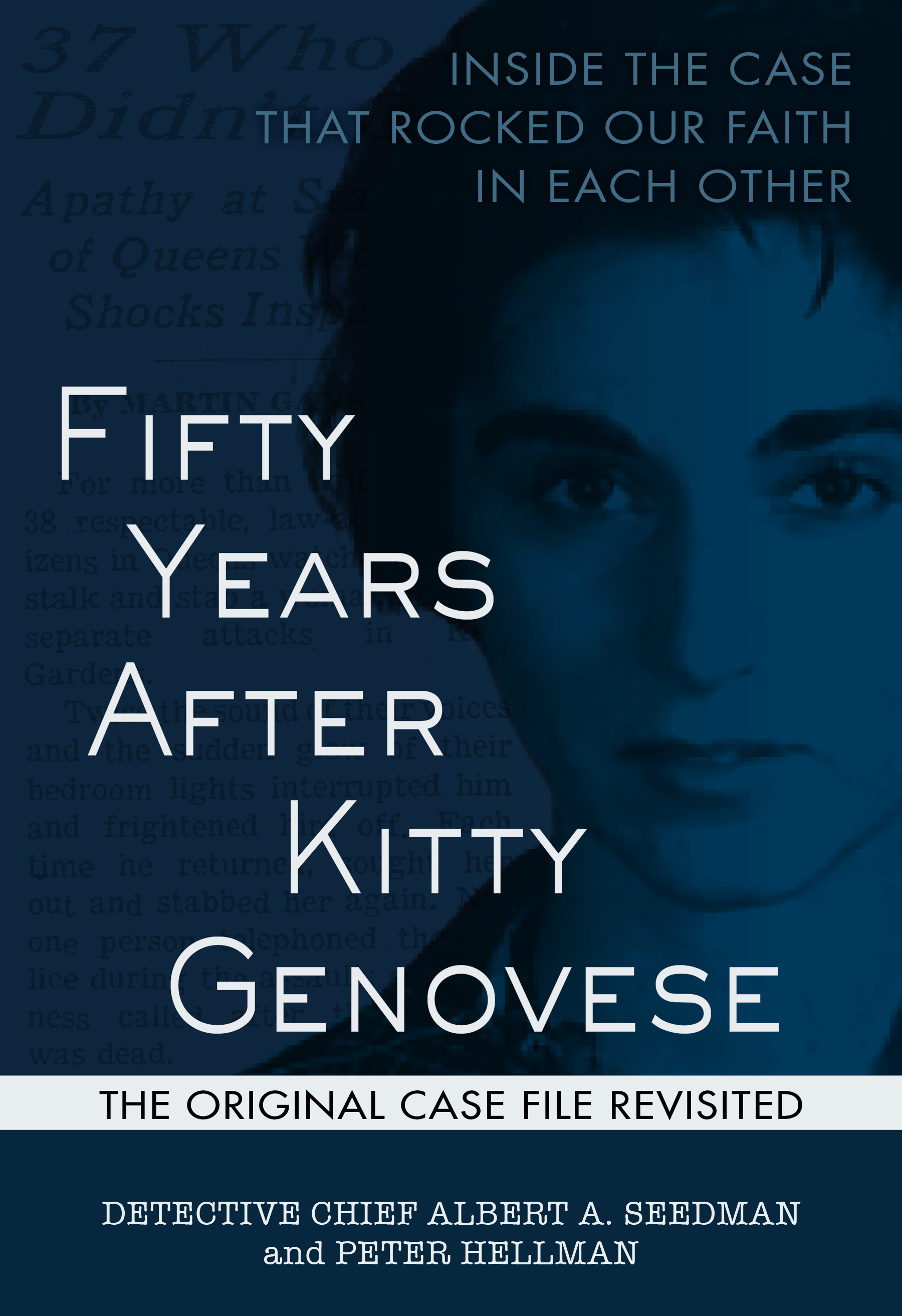

Kitty Genovese was murdered in 1964, exactly 50 years ago this March thirteenth. Twenty-eight years old, she was a petite and energetic native New Yorker who worked as a bar manager and lived in homey Kew Gardens, Queens. Five days after the murder, her killer gave a full confession. But even today, we can’t stop arguing about this seemingly open-and-shut case. Learn why in our newest release (and our first ebook-only title): Fifty Years After Kitty Genovese, by seasoned journalist Peter Hellman and former Chief of Detectives Albert A. Seedman.

Seedman, a legend in his own right, gives a firsthand account from within the investigation, including the bizarre circumstances of serial murderer Winston Moseley’s arrest, the forgotten story of his other victim, Annie Mae Johnson (previewed in our ebook trailer), and—crucially—the detectives’ shock that, although up to 38 of Kitty’s neighbors awakened to her screams when she was first attacked, no-one called the police until half an hour later, too late to save her.

Coauthor Peter Hellman, a veteran reporter who has written for The New York Times, New York Post, and Wall Street Journal, weaves Seedman’s recollections into a taut work of long-form journalism, as riveting today as it was on first publication in 1974 as a chapter in Seedman’s memoir, Chief! Hellman has revised the original for this new standalone ebook edition, and he adds an incisive Introduction and Epilogue that examine whether it’s really accurate, as reported in 1964, that “38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman” but did nothing to help, and why the Kitty Genovese case resonates so strongly even half a century later.

This much we do know: Kitty’s screams at 3:30 AM awoke and alarmed many of her neighbors. One leaned out his window to shout “Let that girl alone!”—at which her attacker fled. But no-one called the police as Kitty walked haltingly out of sight, nor when her assailant returned to search for his victim. It was only after he had found her in the stairwell where she finally collapsed, sexually assaulted her, and fatally stabbed her, that the one witness with a “front-row seat” to this second attack finally called.

It’s true that the witnesses, whatever their number, did not all watch the final act of Kitty’s murder like ancient Romans in the coliseum. But their collective inaction continues to haunt us: One woman dialed police early on, but then felt her voice catch and hung up. Another woman discouraged her husband from doing so, saying, “Thirty people must have called by now.” And, hardest to forget, the witness who finally did call explained his prolonged hesitation with “I didn’t want to get involved.”

The witnesses’ excuses are our answer to “How could such a thing happen?” They are familiar excuses—ones we use ourselves, albeit in the face of lesser crises than murder. That is why, to this day, we are torn between condemning the witnesses and defending them. And that is why we retell the story of Kitty Genovese—not because it’s hard to believe, but because it’s all too easy.